I’m not an expert on brain injury. I am a person who has one. It was an accident — the accident of a drunk with a truck. It was a Code 4 emergency, which means my life was threatened. Then it wasn’t my life. My head hit the headrest so hard it broke the seat. The good news was I survived. The bad news was brain damage.

The drunk driver was Mrs. Cream. This was in 2006, a few years before bashed celebrity skulls and NFL pros splashed “TBI” on the covers of People — and into global consciousness. People was my client then. So were New York and Vanity Fair. I didn’t know what a “TBI” was. Neither did just about anyone else.

A freelance career in media is fairly long if it lasts a heartbeat. I mean a week. Beyond probability, mine lasted thirty years. It had to. I was a single mom — making dinner and deadlines all over the world, perking up headlines while picking up kids.

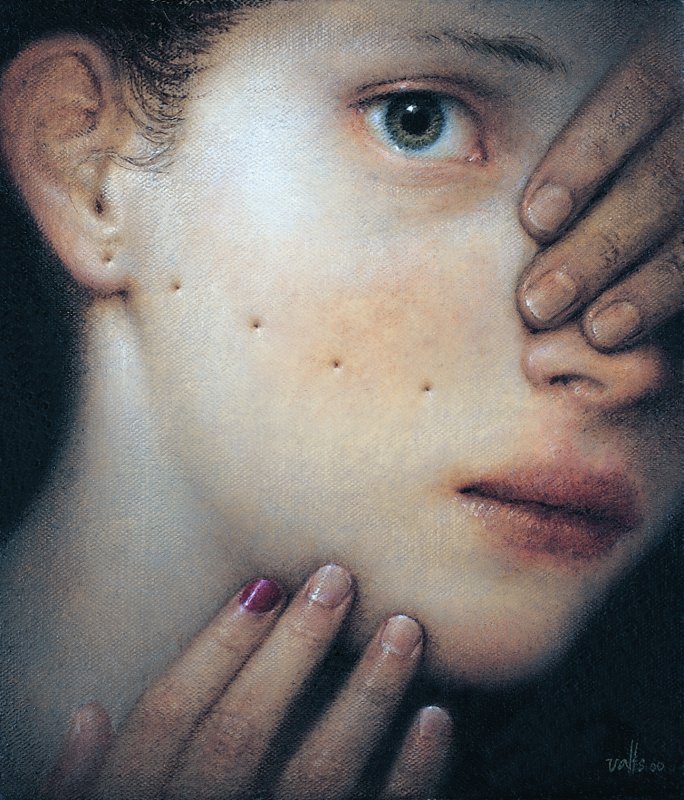

“Forabalis” by Dino Valls

Headlines are not accidents. They are intentional. The perfect hook, the pirouette, the mix of poetry and surgery, boxing and ballet. From baking a Bundt cake to buying a car to dropping a bomb on Afghanistan, we know what to make more of or less of or none of. The right words in the right order, not the wrong ones inside out.

My clients were icons, so they had cash. They got the credit, I got the cash. I wrote ads so Wired would sound, well, Wired, Elmo would sound like Elmo and Elle would sound like Elle. Also, so People would sound like People, Time would sound like Time and Rolling Stone, like Rolling Stone.

Now I am putting pegs in a board.

One moment, I was a head writer in Manhattan, the next I was head injured. Unable to read or write. Movers I can’t recall packed boxes I can’t recall for a trip I can’t recall. I land east of somewhere and west of somewhere else in a rambling wooden farmhouse peering out from tangled brush. The farmhouse is called Avalon, which means Paradise. I live alone. My new address doesn’t show on GPS and is off the Google grid — nine hours south of my life and my child. Where I am does not exist and where I was — is gone.

My head is in a helmet studded with electrodes, a giant eye watching me. I look like a million dollars, rather, a million dots, in a screaming, thumping tube. I’m asked to recall a sequence of two things moments after I see it. I can’t. Then a “sequence” of one. No dice.

Some people get the flu. I got executive dysfunction.

I can’t find words like I used to, can’t line them up and connect them, can’t make them do what I need them to do. I say Dr. Kelly when I mean Dr. Carson or Tuesday when I mean Thursday, show when I mean shoe. Hell, I put on two shows and two socks today.

I didn’t just lose my mind, my life, my child, my mom, my home. Losing “executive functions” means you lose the sequence of steps in a process. Like putting on shoes before putting on socks.

Past, present, and future meld together, like one jumbled moment. Let’s see, there’s breakfast, shower, kindergarten, lunch, college, dinner, movie, childbirth, and career, death of mom, truck, Avalon, friends, shopping, floss and brush.

The human brain contains a quadrillion microscopic connections. That’s one with 15 zeroes (1,000,000,000,000,000) or about the number of ants on Earth. Unless you have a TBI. Then billions or trillions are blown apart.

The frontal lobes are among the most complex and recently evolved parts of the brain — they have vastly enlarged over the past two million years, which is like two seconds in evolution, about as long as it took to dismantle mine.

If you took all the landline phones and all the cell phones in the world, on any given day, the number of calls and the trillions of messages per day would not equal the complexity or activity of messages in a single human brain in a single day.

My brain is numbered. Again. Probes puncture my scalp to survey my mind. Temporal lobe, occipital lobe, you name it; there’s a probe for the lobe. “Measuring” brain injury is like measuring splinters that survived a tsunami. You can’t measure what is lost, only shards that remain. It’s like a series of bombs went off. My child, my mom, my home, my head. Whole neighborhoods blew up in an instant. The neighborhoods were me.

Some people lead diverse, vibrant lives. Writers lead diverse, vibrant worlds.

Every day, we scour a few million sources to shrink subjects of staggering genius into crisp, condensed bits by subtracting the genius stuff.

I keep banging into things. Like Bigfoot with brain injury, or like there’s a magnet in what I bang into and a steel plate in my skull.

The human brain weighs three pounds and has billions of cells and millions of “wires” that let you breathe, think, talk, walk, chop, spin salad greens, spice a mean sauce, sell Girl Scout cookies, take care of your mom, keep clients happy, and clean dryer lint. Or not. Brain damage cancels your plans. All of them.

I lost a piece of my mind and sometimes it shows on my face. I pray that it won’t, but I know that it does. It happens when I have to be somewhere I can’t find or do something I can’t do or say something I can’t say. That’s why I’m in Brain Training. The leader shows us a shiny notebook and says it’s our new best friend. My new best friend is shiny red. Best friends have covers and tell us stuff we used to know. Like what the hell I am doing and why.

I learned as a child it was wrong/bad to “call attention to oneself” or to think of oneself as smart, special, or talented. It was right/good to stay shut in my room, not moving much and not making noise, drawing perfect families.

I drew large, happy, Christian families, naming each child and tucking their age under their feet. Their moms woke them with a kiss. Mine did not. She ran away from home each day to take care of kids who needed her. They were in a hospital.

When I was eight or nine, I found a shoebox, stuffed with tattered photographs. The box was at the top of a closet, likely to keep it from me. Evidently, these were pictures of “family” whose names I never knew. Their lives ended in ovens before mine began. “Family” preceded me on this planet, then were turned into lampshades, then thrown in unmarked graves.

I can’t fix that. I can’t comprehend it. I want to pretend it didn’t happen, and could not happen.

Decades later, I was still a maker of pictures that didn’t include me. A teller of stories that didn’t include me. Even a stellar teller at times. It was almost like acting, except I didn’t play one character for days or weeks or months or years like an actor might. I didn’t speak in just one voice, or from one point of view. I spoke in the voice the audience wanted, which was the voice the client required, until they needed another. I wrote words in mint condition, sparkling, witty, bracing, brisk. I was everyone at once, everywhere at once, speaking in hundreds of voices that weren’t mine to millions of people I didn’t know.

I described wonderful things in short, luscious sound bites, connecting, combining, and cutting so everything fit just right. I knew where to start, how to end, and where to go in between. I knew how many words I needed, the sound of the words, the size of the type.

I could take people I didn’t know to places I hadn’t seen. Places they would love — tucked between perfect covers, like wrapping at Christmas, be-ribboned and gleaming under the tree.

Then I wrote stuff that didn’t include me, made to sound like it did.

Words came in very handy. We ate them at every meal, and they paid the mortgage, too.

When I got a Traumatic Brain Injury, they weren’t making headlines, but I was. Now, brain injuries are making headlines and I am not.

Headlines are important because the brain needs the big picture delivered — in a very small number of words — before it decides if it wants more.

When I was in media, eight out of ten people read headline copy, while two out of ten read the rest. We had to get ten out of nine to read it, instead.

But this piece isn’t about headlines. It’s about being at home on the range, or rather, at home with the range of things that would come up every single day — the unique and unrepeatable combination of stories that would never occur in quite the same way twice: Chicken stock heats up Wall Street. Fish boosts brain. Nuts lessen stress. Dwarfs crash into neutron stars. Gut microbes browse gene buffet.

I lived a carefully organized life amid chaos. Organization was provided by verbs, adjectives, news, views, nouns, and punctuation marks. Plus, all the how-to tips you need. From keeping your hydrangeas from dropping, to keeping your boobs from drooping, from basting a turkey to hosting the best-ever birthday bash, you get the smartest, swiftest, sanest ways to take care of everything — and look great while doing it.

I spent decades telling folks how to prevent everything bad, protect everything important and procure everything good. All they wanted or needed to know, have, want, wear, buy, try, lose, use, taste, sip, skip, slip into or out of.

I didn’t know what I wanted or needed and it didn’t matter at all.

I was paid to telescope huge amounts of information into tiny numbers of words. They had to get the “main point” across and I had to know what it was. It was normal to learn something for the first time and write about it a few moments later.

That gets reversed when you’re brain-injured. You knew something a moment ago, but you don’t know it now.

Just before the accident, I’d started a huge job for a global behemoth known from Burundi to Beverly Hills. The client was told I “hurt my back” and was willing to wait. After three months, not so much. Let’s see. I could tell the client that I’m no longer able to read. No, I can’t say that. I could tell the client I’m no longer able to write. No, I can’t say that. I could tell the client I have no friggin’ idea who they are, what they booked, or what I ever did for them.

I never got another paycheck, never did another job. I refunded the advance. My last career move was writing a fat five-figure check to a NASDAQ company.

The day of the accident, I acquired a “pre-existing” condition, which didn’t exist until just then. It’s serious and incurable. In the first few weeks, it cost $46,817.50. That 50 cents was a nice touch.

Health insurance doesn’t cover being hit by a truck. Neither does “personal injury,” because that requires being hit by a driver with license and insurance, not one who lost them for driving on drugs.

I’m in Cognitive Fitness or will be as soon as I find the room. It is the same room I can’t find five days each week. Curriculum covers how to keep track of several ideas at once, or for beginners, keep track of one idea at a time. Also, Activities of Daily Living, which includes manners, buttons and snaps.

I have been working at this for 5 or 6,000 years and am “approaching getting better.” Speaking of time, the first company I worked for was called Time–Life. It owned Time and Life and People.

There’s no clear demarcation between lives. It’s not like the first life ended on Mile Marker 89 and the second began, and the second ended at Mile Marker Whatever, just south of somewhere and east of somewhere else.

I have a crush on Bobby. I am sixteen years old. He is my first love. Then he dumps me for Debbie because I wouldn’t do it and she would. I’m in Brain Training thirty years later. We are learning which is a cup and which is a hammer and which is a spoon or a bird or a bell.

Every 67 seconds, Alzheimer’s takes up residence in another American. Every 21 seconds, Traumatic Brain Injury breaks another American brain. You want to get back your life, but you can’t — because you are not you, and it’s not your life.

Problems can come to a head, especially a head-injured head. Like you blow-dry your hair and almost spray it with bathroom cleaner. Or put stuff in the blender the wrong way and blast it all over the kitchen or put a fork in the microwave. Or miss ten years of your daughter’s life. She gets a new mom or two who aren’t brain-damaged and says you disappeared.

Life consists of small astonishing moments which defy logic, convention, decorum — and are brave, funny, clueless and clever — all at once or at the same time. So does media.

You can eat a cow and stay healthy, find Atlantis and glow in the dark, while sculpting your 6-pack and having great sex. That’s what I did every day. All at once or upside down. Made headlines and deadlines all over the world. Maybe I told you that.

Media creates suspense, expense, offense, nonsense. We answer questions and question answers, tell shit from Shinola, protect you from blackout, brownout, nuclear disaster, weather wedding disaster, earthquake, Ebola, overdose, bad hair day, carjacking, hijacking, terrorist attack, chemical spill, virus, stroke, and death on Facebook.

I mean what to do on Facebook in the event of death; how to survive the apocalypse without smudging your makeup; and how to make 7,042 meals in fifteen minutes or less. A roller-coaster compendium of what to do and how to do it. How lips and lashes and lawns should look, how you should make lunch and love and millions in Silicon Valley, but nothing in case of a drunk with a truck.

Imagine two groups of people on any subject. One is the group of experts who know it backward and forwards. The other is the group that “doesn’t know it at all.” They’re the same people, only they’re brain-injured now.

We are learning useful skills, like day of week and time of day. Robin forgot the names of her kids. Steve forgot his mom and dad. The new “me” had never read books I used to love, never shared favorite times with my child. I couldn’t remember the sound of her voice or the scent of her hair.

Welcome to Brain Injury Group. We are missing what we used to know and who we used to be.

We come from small towns and big towns, war zone, farms, and factories. I don’t know who’s here because they fell off the wagon or fell off a turnip truck or served in Iraq when a bomb went off. Perhaps we were bakers or builders or teachers or sailors. Maybe we whipped up soufflés or symphonies, grew stem cells, kale, or quarterbacks.

I am more fortunate than many. I still have two legs and two arms, two hands and two feet. One day I counted six of us at the table, but just 9 legs.

Travel is challenging when you can’t read instructions, decipher directions, or know if you’ve gone right or left. So, it’s a big deal that I’m in a cab, speeding through Manhattan. I’m meeting my daughter for coffee, though I don’t want coffee, I want to see her.

The line is long, loud, and in need of latte. Behind us, two girls are preparing an audition. Two guys ahead are talking break-up, while next to us is a budding bromance.

I live southeast of the Blue Ridge Mountains, where decibels like these have not been heard since The Civil War. And where one might perhaps find this many humans dispersed over two or three counties and this much caffeine in three or four states.

I am auditioning for the part of “normal mom,” sort of like I was before. I want to walk like I did. I want to talk like I did. I want to think like I did. I am embarrassed by me.

I’m being tested for the first time in 4.3 minutes. the tester tersely tells me to say words that begin with an “A” when I hear the click.

“Albatross, Abbott and Costello, apricot, apple, Atlantic, Pacific, no, that’s a P.”

Now I must speak in reverse, which means, I must switch “tomato, car, couch, hat” to “hat, couch, car, tomato,” then top that by switching “donuts, dinosaurs, DQ, McDonald’s” with “McDonald’s, DQ, dinosaurs, donuts.” This prepares me to eat junk food and speak backward in real life.

Your brain is how you learn the world. A hodge-podge of stuff from mom or dad or DNA or pre-school or media. You know those weight-loss commercials where someone proudly shows you the pants they used to wear when they were, say, twice, their current size? Sometimes they say, “I lost a whole person.” So did I.

One Comment

Error thrown

Call to undefined function ereg()