The name I’m called, Fay, comes from “Feygela,” little bird. My real name, the name my mother bestowed on me, is FeygaPinya. That double name belonged to newlyweds in Kovel near Kiev, in Tsarist Russia. They were cousins of my mother, one from each side of her family. They were modern Jewish socialists, idealists like Tolstoy, who supported the uprising of 1905 with fiery speeches, but they meant no harm to anyone. When the uprising failed they fled into the vast forest. Someone snitched on them; it could have been in exchange for saving a son from twenty-five years of service in the army. They were found in an old hut at the edge of a Gypsy camp. The soldiers raped and dismembered Feyga before her bridegroom’s eyes. Pinya they dragged back to the town. They rounded up all the Jews and there at the town square, while everyone had to stand and watch, they tied Pinya to the back of a horse, legs up and head on the paving stones, and a cavalry soldier raced the horse around and around the square until his head split open on the stones. Like a watermelon, Mama said.

My mother was still a child when this happened. As the years went by, no one would name a newborn after them lest it bring the baby a bad fate and lest bosses in America would think they themselves were trouble-making socialists.

That meant the story of these brave young martyrs would not be carried into our family’s history. My mother felt so bad about it that when I was born she gave both their names to me. I, FeygaPinya, registered on my birth certificate as Philip Fannie by some unknown person at the Postgraduate Clinic on 2nd Avenue and 15th Street in New York City, I am their namesake, and for as long as I live, they remain always in my memory.

My first nursery rhyme was a revolutionary ditty from Russia. I used to sing it in Tompkins Square Park where Mama met up with her friends. They used to gather under the great old leafy sycamore tree, the first tree on the left as you enter from 7th Street and Avenue B. So many mothers sheltered their children in its shade that it was called the Nursing Tree. Mama would lift me from my perambulator and stand me up on a bench and tell me, “Sing Tsar Nikolay.” It made a remarkable impression.

Tsar Nikolay Yob tfayu mat

Zeyner mit veymen di hust khasena gehat

A koreva, a blata, an oysgetrenta shmata

Tsar Nikolay Yob tfayu mat!

When I got old enough to become curious about the words, my mother told me they meant “King Nicholas, go punch your mother. Look who you married, a girl of filth, a worn-out rag.” She explained that if the King’s mother understood how it felt to be punched she might stop her son from hitting the Jews all the time.

But one day I sang “Tsar Nikolay” in the street to show off to my friends, and a Ukrainian woman grabbed hold of me and waggled her finger in my face and told me never to sing that song again, it was full of dirty words, including the dirtiest thing anyone could do to his mother, even worse than killing her. I ran home and screamed at my mother and stamped my feet. “You made me say dirty words! You made me say dirty words!” But she only laughed. “Every Jew in Russia sang that song,” she said. “Besides, I taught it to you when you were a baby. How should I know you would remember?” Then, when I went back outside, a Ukrainian girl who had been watching told me the real translation:

King Nicholas, go fuck your mother

Look who you married

A whore, diseased, a worn-out rag

King Nicholas, go fuck your mother!

I think that in my mother’s heart she would like to have been the family rebel, a bride in the forest. Instead, she had an arranged marriage in America with a sewing machine operator in ladies apparel and had to make the best of it in the days when everyone struggled to make a living and keep a roof over their heads and raise their children to make something of themselves.

I wasn’t supposed to be born. When my mother broke the news that she was in the family way, she already had three children and was living in a one-bedroom railroad flat on Avenue D and 8th Street with a bathtub in the kitchen, toilet in the hall, and a coal stove for cooking and heating. Maxie was eight, Ruthie was six, Sidney was seven months. My father was beside himself. Where was he going to get more money? Where would they find room for another child? How did she expect to take care of the house with a baby in each hand? But she would not agree to a scraping. She was afraid of infection.

Through an Italian socialist woman in his shop who was active in the birth control movement, he found out about something new, flushing pills. They were as illegal as a scraping, and just as expensive. But he had no choice. He bought them from a druggist down near the docks on the corner of Stanton and Goerck streets. Ma didn’t take the pills; she asked around first and found out that women had died from them by hemorrhaging. When it was too late for my father to interfere anymore, she told him that the pills didn’t seem to have worked. He made her go with him all the way to the drugstore to get his money back. My father, who normally would never get in a fight, was so upset that he grabbed the druggist by the lapels of his white jacket and shook him and called him a faker. Customers had to pull him away. My mother saw that she would have to take responsibility for the fourth child.

On Goerck Street between Houston and Stanton, on the way to the druggist, they had passed a big construction site. A sign on the fence announced:

LAVANBURG HOMES

Sanitary Housing at Low Rentals

For Families of Small Income

Inquiries Are Invited

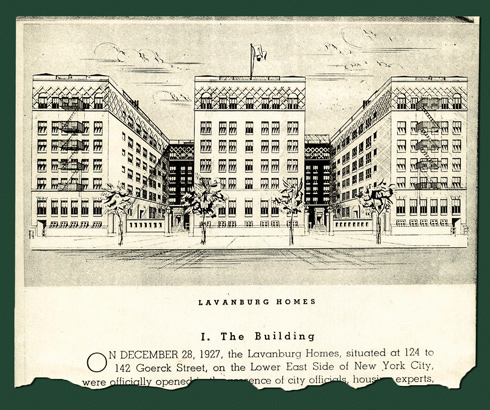

It was signed Fred. L. Lavanburg Foundation. A drawing showed a large modern building with two courts and six entrances. Ma went back the next day, took down the address, and went for an application. At the Foundation office the Administrator, a young man named Abraham Goldfeld, explained that Mister Lavanburg was a philanthropist who had funded Lavanburg Homes as a model of urban housing for low-income working people. He believed that with everyone cooperating, such projects could become self-supporting and could uplift the surrounding neighborhoods as well. The Administrator reviewed the plan for my mother. Lavanburg Homes was to be six stories high to blend in with the neighboring buildings. It would be shaped like the letter E on its back: its two large courts would be open to the street and welcoming to the rest of the neighborhood. There were to be a hundred-twelve apartments with steam heat, plenty of sunlight and air, built-in closets, a tiled bathroom, a laboratory-style kitchen with a dumbwaiter for garbage collection, and a rack by the window for drying clothes; no outside washlines.

There were to be wide, well-lit stairways, a storage room for carriages, a basement social center with meeting rooms and game rooms, a playground on the roof in summer. He told my mother that if her family of six was accepted they would be assigned four rooms for eight dollars a week. This was only a dollar more than the old railroad flat on Avenue D, and was really the same rent because she was paying a dollar a week to keep Sidney’s carriage in the spotless back room of a newspaper-delivery store. It was like a dream! To qualify, applicants had to live in substandard housing and had to show they could keep a clean home and pay rent on time. Also, no child must be over ten years old because the Foundation aimed to raise a new generation of model American children. She answered yes to all his questions and he said she qualified in every respect!

My mother could hardly wait to fill out the application. My father refused. He was a proud member of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union and a negotiator representing his shop. He did not want to declare his income. He did not want to live by the rules of a charitable institution. It was beneath his dignity to have his home inspected. The stand-off lasted months. Every argument between them ended the same, she wailing “You want to bury me,” he muttering “There’s no reasoning with her.”

The opening date for filing applications was July 1, 1927. I was due two weeks later. On the evening of the first, when my father came home from work my mother climbed up on the window sill ready to jump down the air shaft. My father said “You’re crazy,” and signed the papers.

On the morning of the July second my mother rushed to the Foundation office. They already had four hundred families to choose from. Applications were closed.

My mother was only four-foot-seven and she carried big. At nine-months pregnant her belly stuck way out in front of her. This at a time when respectable ladies went into seclusion at the first noticeable bump. Through her Democratic Party District Captain, Mister Dembofsky, she found out where Mister Lavanburg lived. She rang the bell at the gate to his building and asked to see him. A man dressed in a gray suit said Mister Lavanburg was indisposed and would she care to leave a message. She grabbed the fence rails and eased herself onto the ground and said, “I will stay here until I get in to explain to Mister Lavanburg. I have to live in Lavanburg Homes. I qualify in every respect. I am about to have a baby. If I can’t raise this baby in a clean and decent home, I will have it right here on the sidewalk and leave it with you.”

Passersby stopped to watch. A policeman came over. But no one dared touch her, much less try to move her away. So there she sat until a secretary in hat and gloves came out with a note from Mister Lavanburg. She got into a car with a chauffer, the note, and my mother. They went back to the Foundation office. The secretary said to the Administrator, Mister Goldfeld, “Mister Lavanburg would like you to meet Mrs. Bessie Kessler. He thinks she’s just the sort of dedicated tenant the Foundation is seeking.”

I was not quite six months old when Lavanburg Homes officially opened on December 28, 1927.

Mayor Jimmy Walker was there, and Party bosses and urban planners and utopian philosophers and settlement house leaders, and all the new Lavanburg families and all the nearby neighbors, celebrating the first low-rent self-supporting housing project in America. Every speaker pronounced the street name Gork, for G-o-e-r-c-k. The crowd giggled every time, for the whole neighborhood called it Gah-rick. At the end a band played while the Mayor cut a red ribbon. Mister Lavanburg, sadly, had really been sick the day my mother sat down in front of his gate, and he did not live to see his building finished. He was a bachelor and left no close relatives. The first boy born in Lavanburg Homes, Freddy Levine, was named after him. Some people said Freddy would get a college scholarship for bearing the name, but it wasn’t true.

The dumbwaiter shafts conveyed domestic quarrels up and down the line with exquisite clarity…

In the last week of January the streets were alive with tenants rushing to move in, one floor each day so as not to create a moving jam. All but six families came from within walking distance. Thirty-six families were headed by workers in apparel or accessories, nine were headed by sales clerks. There were seven peddlers, seven city laborers. The rest were public transportation workers, truck drivers, taxi drivers, housepainters, plumbers, waiters, bakers, office clerks, postal clerks, two barbers, a butcher, a watch-case maker, a bookbinder, a printmaker, a shoemaker, an auto mechanic, an artist, a photographer, an electrician, a sheet-metal worker, a piano teacher, a Hebrew teacher, a stenographer, a street cleaner, a window cleaner, a rag sorter. There were three hundred fifty children, more to come. Half as many children lived across the street, and more children came every day from nearby streets to this one short block.

Two apartments went to the management office and private quarters of Mister Goldfeld and his German Shepherd dog, and two apartments were rented at a reduced rate to graduate students in social work, three young women in one four-room apartment and two young men in the other. They had been assigned by the University Settlement House on Ludlow Street to settle down among us just like the social workers did in the London settlement houses inspired by Arnold Toynbee: living as neighbors, studying our needs, and helping out in the Social Center.

On my family’s moving day, my mother was so excited and distracted that when Ruthie went to school in the morning she forgot to give her our new address. Maxie and Ruthie went to Public School 15, on East 4th Street near Avenue D. It was an old school with toilet sheds in the backyard. When class let out at three o’clock, Ruthie realized she didn’t know where to go. She stood outside on the school steps in the freezing cold until Ma realized she was missing. Ma sent Maxie back to get her.

As the door to our new home opened, Ruthie was struck by the warmth of the steam heat, by the smooth white walls, by the sparkling new kitchen, by everything smelling so clean. She ran through all the rooms, looked out all the windows, opened all the built-in closets.

Back in the kitchen, Ruthie came upon a narrow drawer in one of the cabinets opposite the sink. It was at waist height and had a crystal knob. She pulled it open. It was lined in purple velvet. My mother came over and stared at the open drawer. She stroked the purple velvet with her fingertips. She told Ruthie it was meant for silverware. She said through tears, “That Mister Lavanburg. That sweet soul. May he rest in peace.”

In the spring, new and used upright pianos began to arrive. One of my very first memories is of being held up in Ruthie’s arms in the courtyard in the midst of a crowd of cheering children, watching as two pianos crawled up the brick walls on pulleys and were eased inside through naked window frames. I remember the very day — the sun was so bright you had to squint to look up — when we stood in the back alley watching a piano being hauled through the dining room window of our own apartment. By the time we ran around to the front and up the stairs, the beloved piano that Mama bought for Ruthie on the installment plan was already in place, adorned with a huge Russian shawl patterned with huge red-and-pink roses, a present from our Avenue C grandmother.

Two Edison Company electric plants, one down below Grand Street and the other over on East 15th, spewed out clouds of black smoke all day long.

Not all worked out as planned. The modern efficiency kitchens, only eleven feet long by seven feet wide, were designed for homemakers to carry meals out to the dining room, but everyone ate in the kitchen as always, squeezing in as best we could at the utility table by the window under the clothes-drying rack.

The oven had to be turned off at mealtimes as it was right up against one end of the table, and the table had to be covered with newspapers when wet clothes were dripping from the rack. The apartment walls were built solid enough so you didn’t hear your next-door neighbors’ business, but the dumbwaiter shafts conveyed domestic quarrels up and down the line with exquisite clarity and were put to use as listening posts. Nor was Lavanburg Homes to be quite the promised sanitary haven, for the dumbwaiters were only one of several convenient routes by which mice and cockroaches found their way into and among the new apartments. Bedbugs, lice, and those huge horrible waterbugs also invaded the apartments, just as they did the rest of the Lower East Side.

Patrons of the American settlement house movement often toured Lavanburg’s. They commended the cleanliness of the hallways and courts. Mister Goldfeld’s “deputy commissioners,” a volunteer patrol of bullies among the oldest boys, saw to that — but they must have been disappointed to find the new generation of children as dirty and ragamuffin as the rest of the East Side kids. They never came on weekends when we were clean and all dressed up; they only saw us after school when we got into old clothes so we could play in the street.

From “Practices and Experiences of the Lavanburg Homes, Third Edition,” (Fred. L. Lavanburg Foundation, New York City, 1941). Used with permission.

One time Mister Goldfeld escorted some ladies out of the court while the boys were lined up along the curb seeing who could pee the farthest. The ladies pretended not to notice. Mister Goldfeld rushed to the curb to stop the boys. Just then the seltzer man’s horse, Danny, claiming the territory the boys had invaded, started a great splosh of pee on the cobblestones right in front of him. Mister Goldfeld barely jumped back in time. He got the giggles, and soon the ladies and everyone else were laughing their heads off, except the boys, who were struggling to button up their pants.

But it was really the coal dust that made us look bad. Two Edison Company electric plants, one down below Grand Street and the other over on East 15th, spewed out clouds of black smoke all day long. Our Lower East Side streets nestled in the bottom curve of Manhattan island and weren’t exposed to the wind currents that swept the uptown streets clean from Hudson River to East River. Our clouds of soot whirled about willy-nilly. Coal dust and grit got all over us, our hands and faces and clothes. Mister Goldfeld used to call us his angels with dirty faces. It became the title of a movie that had nothing to do with us.

On windy days we would get cinders in our eyes. From our earliest years we knew how to pull our upper lid over our lower lid and let the lower lashes wipe the cinder away. But if one of us got a speck that wouldn’t come out, the whole gang would cross the street to Doctor Gelman’s drugstore on the Italian side of Goerck.

Doctor Gelman was a kindly man with steel-rimmed glasses and thinning blond hair. We had no fear of him even though he wore a starched white jacket. He would roll a bit of cotton onto a fine stick, and then he would stand you on a chair and ask your name before he started.

He would flip your upper lid inside out with the side of the cotton stick, and when he got the cinder out he would give you the stick so everybody could look at it and see how big the speck was. If you asked him, he would flip both your eyelids for you so that the pink part came half-way down your eyes and you could stagger out of the drugstore like the Frankenstein monster with your hands drooped in front of your wrists. Even if you didn’t have a cinder you could go in and ask Doctor Gelman, “Make me into Frankenstein?” and he would do it for you.

Doctor Gelman wasn’t a real doctor but everyone called him that out of respect. He seemed to especially like me. When I came in to have a speck taken out, he would roll out his piano stool from behind the counter and give me a twirl on it, and he’d give me and my friends chunks of rock candy for free. One time I was watching the coal go down the chute to our basement furnace room when the wind came up and I got cinders in both eyes. My father was standing by the ash cans when this happened, and he brought me in to the drugstore. When Doctor Gelman finished, he ruffled my hair and said to my father, “Look at these pretty curls, like Shirley Temple. Aren’t you glad your Missus didn’t flush her away?”

Upstairs in the house, with two cotton sticks in one hand and a piece of rock candy in the other hand, I said to my mother, “Doctor Gelman said you almost flushed me down the toilet.”

And that’s how my mother told me the whole story of the flushing pills, up to the part where my father almost beat Doctor Gelman up and she saw the sign for Lavanburg Homes and got us in with her sit-down strike. When she was finished I asked, “Is that why you named me after the unlucky bride and groom who got killed, because Papa didn’t want me to be born anyhow?”

“Oh, your child’s head has it all twisted around,” she said. “First of all, as soon as Papa saw you he changed his mind, because you were such a nice beautiful baby. Second of all, because you were almost not born, that means you were lucky to be born. You were born lucky. So that’s how I got the nerve to give specially to you the names of Feyga and Pinya, because you already showed you had a good fate. And don’t forget, even before you came into the world you brought luck and a good fate to the whole family. If not for you we would still be buried in that miserable grave on Avenue D and we would never have come to live in Lavanburg Homes, may God protect it.”

7 Comments

Error thrown

Call to undefined function ereg()