There are usually a few days during every English summer when the jet stream brings settled high pressure and the prospect of wind and rain recedes for a time to the continent. This day was one of those. The sun came up with confidence and intent and set the prevailing conditions, with little chance of damp influence by wind gusts and precipitation. It was the middle of the summer holidays and doldrums were approaching, when the novelty of free time stretching with no apparent end was over, and the family holiday in August loomed ahead as a less-than-attractive prospect. From what I can recall, this was a time when I had few if any close friends, or those that I did have were already away on holiday to Cornwall, Blackpool, or, for the relatively affluent, the Spanish Costa del Sol. This was the early nineteen-seventies, a time of growing social aspirations for the English lower middle classes for which a foreign holiday provided a sure indication of upward mobility.

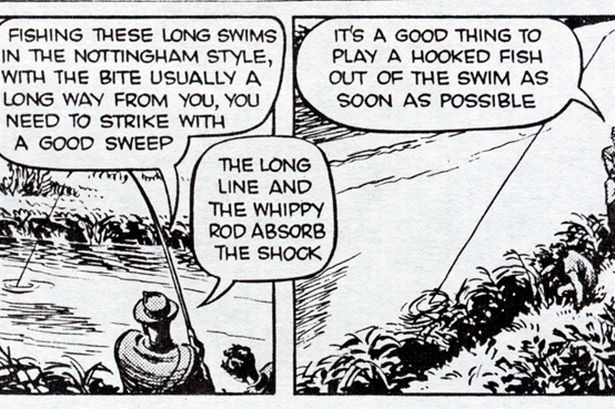

Panels from “Mr Crabtree Goes Fishing” via The Mirror

I had woken up alone in our house and I wandered around from room to room not quite knowing what to do with myself and a sense that I didn’t want to waste such a unique day. I am not sure how I arrived at the idea to ride my bike to a place on the River Clyst and try for a trout I knew would be catchable at a bend in the river upstream from Clyst St Mary. The plan combined several factors that appealed to me — the freedom of a bike ride never previously undertaken, the opportunity for solitude in an attractive and peaceful rural setting, plus the chance to fool a large trout into taking my bait. It also gave me a chance to discover for myself how my grandfather’s commute by bike, rain or shine, from Clyst St Mary to the bakery in Exeter really must have been like. I didn’t know my grandfather, he died a few years before I was born, but I have pieced some of his life together from family folklore, photos and recollections. My grandfather, Harry, was wounded in the battle of the Somme in the First World War and never fully recovered from the gunshot wound that would not heal, troubled him for the rest of his life and eventually killed him. Relevant to this story, however, is that after the war he biked the eight miles each way every day to work nights in the bakery, came home in the morning, took a nap, went to the Half Moon next door, drank lunch, and went to the river to fish when the weather cooperated. He usually fell asleep on the river bank and was fetched from the river by my father returning from school. Harry’s schedule became etched in family history, as was a story about him being chased when riding his bike home early one morning along the bridge over the Clyst estuary by a Messerschmitt returning from an attack on Exeter. The story was never verified, and Harry had a reputation as a gifted and creative story teller of fertile imagination, especially with the assistance of a lunchtime spent in the pub.

Harry was therefore a drinker, a cyclist and a fisherman — so the idea to resurrect a day in his life — minus the liquid lunch — seemed better than anything else I could think up.

The local fishing population used to fish the River Clyst during the angling closed season because it was tidal and not bound by the same rules as other fisheries in and around Exeter. The Clyst wasn’t full of fish, but provided the only river fishing available from April to June, and consequently attracted numerous teenage fishermen with nothing else to do during the spring. The river was accessible by walking across several fields that in April were invariably ploughed in preparation for spring seeding. The soil was a complex clay mix with the consistency of pizza dough that I can’t help but think reminded Harry of the trenches. I have walked across those fields in early spring carrying my own version of a kit bag comprising a fishing creel and rod bag and found with every step an extra pound of mud attached to my boots. Soon walking became impossible, so you had to stop and scrape off enough layers to permit any hope of further progress. The furrows were also more than a foot high giving the impression of walking uphill wearing a pair of diving boots more at home on a character in a Jules Verne novel. The only difference I can determine between me and Harry in the muddy fields of Clyst St Mary or Flanders was that I wasn’t likely to be hit by a round from a sniper or blown to pieces from well-placed ordinance while going fishing in Devon in the seventies.

Mr. Crabtree shares his piscatorial insight with passion, a certain degree of mysticism and a way of talking that conveyed the air of a public school classics master.

The more I consider Harry’s fate in the Great War, and he was one of the fortunate ones, I ponder how good timing, or lack of it, affects us. Harry was only two years older than my son now when he volunteered, and I can’t imagine my son heading off to an uncertain future in an incomprehensible war, and from which he had little chance of returning intact. I did not know Harry, but I imagine he was profoundly affected by his experience and know it subsequently helped shape my father’s personality. I have wondered if Harry ever thought with enmity of the German rifleman or machine gunner who fired off the round that burst through his leg, resulting in him being invalided out of harm’s way. Perversely, this bullet more than likely saved him from a bleaker future than if it had missed and he had remained to take his chances for another year on the western front.

My odyssey to the river Clyst took place in July. The barley was well-established in the fields, and the smell of rural summer travelled with me as I pedaled over the old Clyst bridges. I continued past the Half Moon, decided not to test whether the landlord would serve a pint to an underage drinker, and headed down to Holman’s garage and the path to Sowton. Holman’s garage used to be a mill, and in its heyday the mill race would run fast and full from the main river providing power to turn the mill stones. The mill had seen its fair share of tragedy, as my father as a boy witnessed a small girl drowning in the mill leat. He had been playing around the mill and had arrived to see the little girl trapped underwater and drowned, drifting in the current. He was too late to do anything and had returned to the village to get help and encountered the little girl’s parents on the way. The River Clyst and Clyst St Mary have some historical significance. The village had been the location of a bloody and murderous battle during the prayer book rebellion of 1549, and the execution of several hundred rebels, some by drowning in the river, is well chronicled as an example of the brutality of religious intolerance that was eerily out of place in this sleepy corner of rural England not usually known as a hotbed of religious fervor.

I dumped my bike in a hedge by Holman’s garage and recall the heat of the day blasting a confusing smell of diesel oil, grease, old tire rubber, dried cow manure and summer cereal grass as I walked along what remained of the silted mill leat and beside the river bank away from the dam that marked the limit of the tidal river. The river from here upstream was private and owned by the occupants of Bishop’s Court. Fortunately the river was rarely patrolled, and if you were prepared to keep well hidden, you could enjoy some good sport with the remaining trout that had been stocked a few years previously. A rumor circulated that a trout had survived and grown large under an alder bush at the bend in the river. The fish had even been named. “Moby Dick” he was called, and although this may have been something of an exaggeration, his reputation had grown large, fed on youthful imagination. The bend came into view and I quietly placed my duffel bag down and set up my rod with a small stick float and a size 14 hook with a fresh worm as bait.

Harry and I had missed each other by about twenty years that day on the bank of the River Clyst, but looking back on it there was clear purpose in me being there. I lay back in the long grass and looked up at the lonely cirrus clouds wandering across the intensity of a pure blue sky.

“Be careful to approach the edge of the stream with caution and make sure your silhouette does not show against the sky,” I imagined Harry saying.

“The trout is a magnificent fish and a worthy adversary. There is no better fighting fish and one of a pound or more will certainly test the tackle you are using.”

“Look, son, see how the current comes around the bend creating an eddy of slower water under that bush. I’m sure your trout is lying there waiting for food to flow by. You’ll need a perfect cast to get past the main current without tangling in the overgrowth. A worm should be the right bait; make sure it’s fresh and kept in a bed of moist moss.”

I flicked my line across the stream and under the far bank. The float stood up in the small eddy for a couple of seconds, then dipped; I struck and a beautiful brown trout leapt out of the water and headed for the far bank.

“Turn his head or you’ll lose him in the alder,” a voice advised me and I put as much side strain as I dared and the fish was persuaded to move back into the stream. A couple of minutes later I had him on the bank, not quite Moby Dick, but a nice fish of a pound and a half.

“He put up a worthy fight, but he’s the perfect size for the pot, so we’ll wrap him up and see what Betsy can make of him.”

Back then, my favorite book was Mr. Crabtree Goes Fishing, as it was for thousands of young fishermen in England. The book contains a series of cartoon captions depicting various outings of Mr. Crabtree and his young son Peter angling for various species of fish (for context, their cook was called Betsy). Mr. Crabtree is never without a pipe and is dressed usually in a jacket and tie. He has a vast knowledge of fishing techniques from the 1950s and 60s and shares his piscatorial insight with passion, a certain degree of mysticism and a way of talking that conveyed the air of a public school classics master. To me this man was the pinnacle of fishing elite, and I can now see how Harry could have been my own personal Mr. Crabtree, if only he had dodged that bullet in 1916.

Harry would have fit the bill nicely, probably with a few embellished stories and some illicit beer drinking thrown in, but he died early and it fell to an uncle of mine to become my actual Mr. Crabtree. Our fishing friendship started when I was about eight years old, and of some relevance to this story, Bishop’s Court had a key part to play.

He took part in the liberation of Norway and may have been present at the Yalta conference as an aide to the British delegation.

Uncle Bert knew the owner of Bishop’s Court in the late sixties having done surveying work for him at some point. Bishops Court had been the summer residence of the Bishop of Exeter since the 13th century, but entered private ownership more recently. When I knew the house there was a Spitfire standing beside the poplar-lined driveway, as the owner had been an RAF pilot. The house itself was full of dark wood paneling, large oil paintings of long-dead bishops and weighty leather-bound tomes in a library that had more square feet than my house. A quirky clause in the purchase deed ensured that any new owner of Bishop’s Court kept the furniture and decorations in place in perpetuity, a fortune hanging on the walls and shelves kept there by a handshake, a gentleman’s agreement and the threat of possible legal recourse.

Bert and the owner were well enough acquainted that he was able to gain permission to fish in the lake adjacent to the big house. Permission came always in the form of a handwritten letter, in perfect copperplate on expensive eggshell-blue bond. The lake was situated in the middle of an untidy copse surrounded by overgrown trees and tangles of thorn bushes. A collapsed boat house with a sunken punt decayed in one corner and branches stuck up from the surface of the water over much of the surface. Broken branches were not the only thing the pond contained. It held an old, neglected but healthy population of very large carp, and that was what interested us. We were the first people to fish in the lake for a generation and besides the large carp, we had no idea what else the mysterious depths near the dam contained.

We would get to the water early, frequently crossing a pasture carrying our rods and creels through mist clouds floating around the base of the valley, rising slowly off the water. Bert was the husband of my father’s sister. He was a Derbyshire lad, who volunteered to be a fighter pilot in World War Two but was color blind and therefore spent the war stationed in Iceland, where the monochromatic landscape posed little challenge to his limited color perception. He took part in the liberation of Norway and we think was present at the Yalta conference as an aide to the British delegation. Bert was always impeccably turned out when fishing. Harris tweed jacket over plaid shirt and wool tie, well pressed khaki trousers, highly polished brogues, or green wellingtons if muddy, and of course a deer stalker. In rain he wore Barbour. These were times in England when the type of fishing you undertook depended on your annual income and social class. Bert’s attire would have been more at home on a gentleman casting an upstream dry fly on the manicured banks of a Hampshire chalk stream, but to me he didn’t seem out of place beside our overgrown pond, fishing with worms.

Bert taught me knots, the right type of float to use, how to rig up a rod, the correct hook size for different bait and fish species, and where to find the most likely holding spots for fish. He was an excellent and patient teacher. This was his profession, but fishing can be a frustrating subject to teach, even for a professional and often requires an ability to climb trees to retrieve tackle and some aptitude with untangling complex nylon monofilament birds-nests that become firmly attached to reels. Bert’s ability as a fishing coach was supplemented in one very important way. He owned the first edition of Mr. Crabtree Goes Fishing and I would read the book cover to cover every time I stayed with him. I learned a lot from this book, and it didn’t require too much imagination to see Mr. Crabtree and Peter re-cast in me and Uncle Bert. I use the information newly learned on our outings to the pond even now, and Polaroid snapshots of the time showed we had our fair share of success with the carp. One evening, I recall very vividly, we decided to fish from the overgrown and deep side of the lake containing the most complicated tangle of submerged trees and branches, as Bert thought that is where the largest fish would be. He turned out to be right as he hooked a very large fish that he was unable to prevent wrapping itself around an ill-placed branch. The fish had charged straight at the bank where we stood, then reversed course before returning to its sanctuary on the other side of the branch. Bert retrieved his broken line as the light faded and the evening darkened around the pond in the wood and I recall a feeling of unease being a small boy beside a lake that was home to some unusually large animals, and also a strong sense that I really didn’t want us to lose our way out of the copse, and stumble into the dark and uninviting water.

We fished the pond on and off for a few years. We were the only ones with permission as it was private and unknown to the local fishing youth, and was patrolled vigorously by the local farmer. Back then, in the late sixties, the pond was in a state of disrepair and had started to silt-up at one end. I frequently wonder about its subsequent fate as I have not returned since our last outing and I now live a continent away. I want to think that the pond was frozen in time and that I could drive out to Bishop’s Court, walk across the field and find the pond overgrown and full of carp, much as we’d left it. I have a recurrent dream however, that the lake has fallen — victim to progress and that the field has been sold for development as single family homes, or worse, an industrial park. I fantasize the lake has become a depression in a car park and the carp are incorporated into a concrete foundation. Perhaps the lake has been sold to a fishing club and the copse has been cleared and the banks cleansed of overgrowth. Perhaps the boat house is restored, the lake deepened and debris dredged out. A club ticket and a local fishing license allow you unrestricted access to the stocked pond, and at the weekend it becomes difficult to find an open stretch of water in which to cast a float. George Bowling in Orwell’s Coming Up for Air experiences a similar unfortunate circumstance. He returns to a secret pond hidden away on a private estate twenty five years after finding it full of huge carp, only to see it reduced to a refuse tip used by a housing estate that had sprung up close by. Orwell uses the literary image as an indictment of urbanization and growth, and there is clearly an implied reference to the unsettling prospect of his pastoral English heritage being overtaken by a totalitarian and sharp-edged future. Orwell’s book was published immediately pre-war in 1939.

Even though we lived an ocean apart, Bert and I fished together at least once a year for the rest of his life. He always caught more than I did, and I suspect held this as a source of pride as he slowed down into his 80’s. He continued to drive his Rover at full speed around the Devon lanes as he headed to his favorite trout fishery and I could never keep up with him. I received an early morning call from my cousin to let me know he had passed away and I read his eulogy in his local village church. I did not have the courage to include a pilgrimage to the River Clyst or Bishop’s Court when I returned to England for Bert’s funeral, but I have just tapped the screen of my I-pad a few times and have been able to focus down on the grid reference where the field and the pond used to be, using the topography function of MapQuest.

I didn’t realize it at the time as I pedaled home that day in 1974 with the brown trout warming in my duffel bag, but over the years since then I came to understand the broader significance of my day out on the banks of the Clyst. In a sense it brought me as close as I could possibly be to Harry, and as I reflect on that day forty years later with fading memory I almost bring myself to believe he was actually there. It offsets to some extent a feeling of loss of not having known him that seems to be getting more intense as I approach the age at which he died.

8 Comments

Error thrown

Call to undefined function ereg()