Jesse was a beautiful boy. Fair-haired, eyes of indeterminate color — blue or green, it depended on the light. My favorite of my daughter Greta’s friends. I still remember the sandcastle we built, our last summer at the shore. A marvel of engineering, with a curtain wall and battements. A drawbridge we’d fashioned from rounded pebbles and the lost halves of bivalves. It took us days to build, hauling up sand from the tide line — hard-packed sand, the best fortification.

He died, suddenly, in his twenty-first year.

“Jesse’s dead,” Greta mentioned, before going on to mid-terms and transient love interests, the dross of college life.

“How?” I asked.

“Drugs, I guess.”

I hadn’t seen his parents for a number of years. They divorced, like we divorced. The person you married inevitably turned into one you could never satisfy. A person who endured you, and humored you, instead of loving you. A person who slept huddled on her side of the mattress. A person who said not now, and turned off the lights mid-conversation, not caring, not really, about what you had done that day, or the ache in your back, or your inner demons, already tuned out, static.

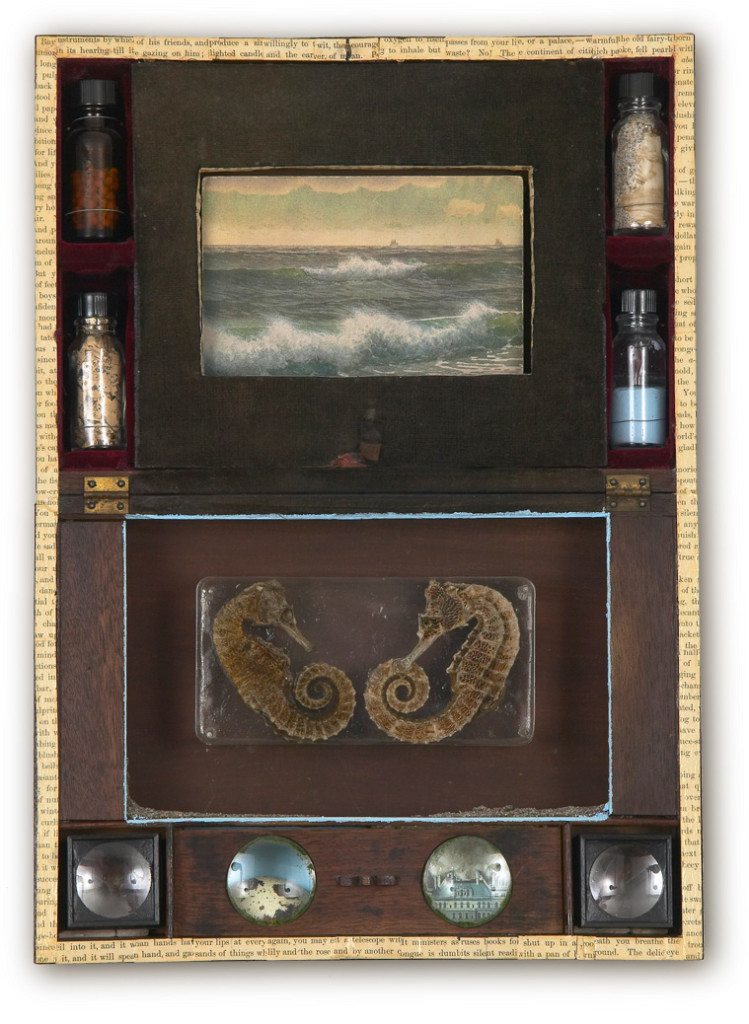

Hotel IV by Brian Booker

Not everyone divorces for the same reasons, of course. Ours, at least on paper, were constructive abandonment, irreconcilable differences. Legal speak for extra-marital lapses and unspecified bad behavior. In my case, mistresses whose names I no longer remembered; transgressions the details of which remain hazy. Amelia served me with the papers in Muldoon’s Tavern. Knew my habits well enough to know that’s where I’d be found, whiling away the afternoon, reading Heidegger or Kant and throwing back a few.

“Jesse’s dead,” I told Amelia.

“I know,” she said. She’d long ago remarried. Her husband, Bob, earned the requisite salary and let her run the show. The fact that he was deathly boring, and spoke passionately about the LIBOR index, did not dissuade her from agreeing to marry him.

“What happened?” I asked. “Or do you not care?” I sensed her centering herself. Telling herself not to revert to the usual patterns, the dysfunctional repartée of our marriage. Reciting Buddhist crap. Regrounding herself in the now.

“He’s dead,” she sighed. “Isn’t that sad enough? Why do you need to know the lurid details?”

“Isn’t it natural?” I asked. “One day, you’re twenty-one years old and vital, and the next, you’re no longer of this sphere?”

“It was drug-related, I’m sure.” Jesse had been in and out of rehab. Spent three months on a cliffside in Big Sur, rewiring his brain chemistry, trying to convince himself of the merits of sobriety.

“Of course you’d make that assumption.” Amelia believed all of us responsible. No allowances for human frailties, for deficiencies of any kind. No mercy for those who faltered, stumbled off the path, or unaccountably imploded. Of which cashing in my partnership equity, and renouncing the practice of law, apparently qualified.

“He was a heroin addict,” she said. “They don’t have long life expectancies.” As if the culpability of the participant robbed the event of its tragic dimension. As if the flawed weren’t worthy of our sympathies.

“When is the service?” I asked. I imagined Jesse as a boy, frolicking in the waves. Making castles from hard-packed sand. His eyes luminous in the sun.

“When is the service?” I asked.

“Don’t make this about you,” she said. “It’s not about you.”

“I’m not,” I assured her. I snuffed out my cigarette, and ripped the nicotine patch from my shoulder. No use engaging in the pretext. I wasn’t quitting any time soon.

The obituary in the local news simply informed that he had died on such-and-such date, no cause of death indicated. If he had died of childhood leukemia, or if he was felled by a drunken driver, he would be instantly vaulted into the pantheon of fatally stricken youth, youths with foundations and colorful wristbands, youths whose foreshortened lives reflected poorly on us all, on our commitment to cancer awareness or better highway safety. But he had a hand in his own demise.

We divorced when Greta was thirteen. Not the best age to learn that men are pigs…

I wrote a note to his parents, though I hadn’t seen either in years. I debated whether to address them jointly or separately, whether to pluralize the tragedy. Dear Deb and Mark, I decided upon. I heard about Jesse…. I faltered. What do you say to those whose undergirding has come apart? Who must go on, nonetheless? Nunc pro tunc, as if they’d never had a child, as if they’d never fussed over him, and disposed of soiled diapers and sent him to school and watched apprehensively as he crossed the street and silently prayed that no harm would ever befall him?

I will always remember him as the fair-haired boy in the sun, I wrote. Proud of myself for avoiding the clichés, I’m so sorry for your loss, he’s in a better place, all the things we tell ourselves in order to believe that death will not prevail in the end, that a glorious afterlife awaits — at least the virtuous among us.

We’d built the sandcastle, patiently, over the course of weeks. It had impressive towers. It withstood several bouts of rain, only to wash away during one torrential storm. We arrived to find it in a shambles, the watchtower toppled and the moat flooded. Jesse cried. Said What’s the point?, or Why bother?, something to that effect, and stomped off.

Dear Deb and Mark,

Words escape me. What can I say? There is nothing I can say that will make it better. I remember him as the boy in the sun. Building sandcastles.

Amelia made off with most of the friends post-divorce (as well as the brownstone and half my retirement account). They’d sided with her, pledged fealty to her, and, freed of the need to spare her feelings, felt they could speak freely on the subject of my transgressions. We hadn’t wanted to tell you, but… Now that you’re getting divorced, I thought you should know, all kinds of lurid unburdenings and salacious errata. I don’t know if you realized, but… Hadn’t you a notion deep down?, that kind of thing. Once we announced our separation, a trap door opened into a hidden world.

It was Deb, in fact, who revealed I’d been having an affair. She and Mark had seen us together, on Bleecker Street, embracing in public. They decided, at least initially, to err on the side of secrecy. They didn’t want to be judgmental. But they felt morally compromised. It affected our friendship. They shot looks at me while I barbecued, appalled, somehow, that I could carry on so naturally at home, You like medium rare, right, Mark? Can I refresh your vodka tonic? You like a twist, right?

It wasn’t anything serious. It never was. Just a passing fancy. A detour from the long stretches of matrimonial road. Youth ebbing and a hardening taking place. The slow chipping away of sanity. If you do not segregate the recyclables we’re going to get a ticket. The desperation to breathe, to feel alive, as opposed to merely subsisting.

Amelia is a real estate agent now. Deb gave her the idea. Said it would be good to “earn her own money.” Now all she talks about are zoning variances and the perils of wet-over-dry construction. Rhapsodizes over the period details in brownstones. Positively creams over original wood paneling.

“Do you think we ought to send them something jointly? Flowers to the chapel?” I inquired.

“Why would we do that?” she sighed. “We’re divorced.”

“Why?” I asked. “Don’t you think it would be a nice gesture?” An homage to the past, to what we once were.

“We already sent something.” She and Bob, and presumably Greta, only I had been excised from the equation. She had my things in cartons before the separation was even official. Told me I had a week to pick up my belongings, else they would be sold, or disposed of, because she had no room to store my things. I’d been cropped at the margin of photos. My presence edited out. Just a hand, or an arm, or the intimation of a shadow.

“Of course you did,” I sighed.

“Don’t forget to pay your half of the tuition,” she said, before hanging up.

I’d seen something in her once, I suppose. Something beyond the call of pheromones, the hard-wired responses. Something that transcended the usual she’s hot as hell and I want to bang her. She was rapturously beautiful, the line of her body and the curve of her hip and the soft indentation of teeth on her lower lip. She trembled after she came: every nerve fiber alight, alive.

We divorced when Greta was thirteen. Not the best age to learn that men are pigs, that what you believe to be true and irreducible in your world – the fundamentals of mother, father, marital union, etc. – is in fact an illusion, a carefully-constructed reality, not to be believed. Your dad slipping out during intermission, living in the ellipses.

“How are you holding up, pumpkin?”

“I’m fine, Dad,” Greta sighed. She had her mother’s practical streak: why obsess over things we cannot change? Why struggle with unruly emotions?

“Be that as it may, my sweet, you must feel something. Better to talk it through.”

“We weren’t even close, Dad. I hadn’t seen him since we were twelve.”

“Still, you were so close back then.”

“We were. But I really didn’t know him anymore,” she sighed.

I cannot attest to Jesse’s merits as a songwriter. I cannot vouch for what was in his heart. I cannot know what he was thinking as he tapped the vein, one last time – of the cat on the ledge? of a girl who had rejected him? I know nothing of the moment when the heart seized, no longer able to maintain a rhythm. The dividing line between the sentient and the dead, between what we know and what defies us.

“It’s got to be difficult,” I ventured.

“It’s just weird,” she trailed off.

We never had a custody battle. No skirmishes over visitation, or where to enroll Greta for summer camp, or what she was going to do for spring break. No dilemmas about where she would spend the holidays, in whose sphere she would remain. I couldn’t even purport to be the better parent, the better influence, the stable presence. Amelia ever so kindly referred to me as a spendthrift and a serial philanderer, if memory serves me right. I was never sure what was worse, in her eyes, my fiscal lapses or my adulterous ones. I think my affairs, in some ways, were a relief. She didn’t have to feel guilty about ignoring me, or engaging in the most perfunctory of sexual relations, rolling over as soon as I had spilled myself inside of her, detaching herself from me, and turning out the light. Not so much as an emotional ripple, a howl, a guttural exclamation. But the fiscal lapses were unforgivable. The first time I was unable to write a check to the Leighton academy, she called me abysmal. An abysmal father, a poor excuse for a man.

“I think you ought to consider not going.” Amelia called me.

“What?” I replied, incredulous. “You can’t be serious.” I’d seen Jesse grow, and now I’d seen him die, a blinding flash.

“I just don’t think it would be a good idea,” she softened.

“Come on, Amelia, we all got on well.” I motioned to the bartender for a refill. Jesse’s death had broken me. Made me weepy, ungovernable, emotionally incontinent. Left the bracken exposed.

“Maybe for a time,” she said, wistful. “Maybe for a summer or two at the shore. But you put them in an impossible position. You have to admit that.”

You have to admit that. The incontrovertible. The patently evident. Stipulate to the fact that you were having an affair. Banging her on the divan, not even bothering to shield the world from your transgressions. Implicating them, making them feel uncomfortable, letting them assume the weight of your deception. Etcetera, etcetera.

“I didn’t ask them to lie for me,” I asserted. Though, of course, I relied on a certain amount of discretion, a willingness to look the other way, the assumption that saying nothing would be better for us all. I had a hard time even remembering her name.

“Still —”

“I want to pay my respects,” I protested. I wanted to see him one last time, the fair-haired boy I remembered. Though he’d long ago stopped being that, though his skin had purpled and bruised, and his veins had collapsed. Though we’d long ago stopped being a family, though the shore had been battered by successive hurricanes, though mold had overtaken the basement, rendering the place uninhabitable — at least according to the insurance company inspectors who make such determinations, unfit for human habitation, check.

“He wasn’t the boy you remember,” Amelia said.

“I know,” I trailed off. The clock ticking. It would soon be Happy Hour, before people returned to their families, to their commitments. The interregnum before dinner, when all was possible and love was refracted through shot glasses, and hope filled the air.

“I know you mean well,” she said. “But it’ll be awkward. Why don’t you make a donation in his name? They’ve set up a fund.” A fund for the derelict, the irreparably broken-down, those of us who’ve lost our way. Those with track marks and gnarled veins and bruises.

“I’ll do that,” I concurred.

“His bandmates sang Hallelujah,” Greta called. I was in Muldoon’s, as per usual, whiling away afternoon. “They’re going to release some of their old jam tapes.” Death Trapp or Flaming Doom, I’d forgotten the moniker. Young people had an affinity for apocalyptic names and morbid sentiments.

“Well, it sounds like they gave him a proper farewell,” I said. A send-off befitting his life. Full of bombast and off-pitch carnage.

“They had a collage,” Greta said. Photos someone, likely Deb, had put together. “There was a picture of us from the shore,” she trailed off.

“The sandcastle?” I inquired.

“No, just of all of us on the beach.” Backlit, the waves lapping around us. The water an impossible blue. Before the refuse washed ashore, before water infiltrated the foundations.

My companion was growing bored. She was too young, too tipsy, on the impractical side, just how I liked them. I put a finger to my lips to silence her. “It’s my daughter,” I mouthed, hand over the receiver.

I don’t know why I felt it incumbent on me to whisper. I’d no reason why I needed, any longer, to be furtive. To take my calls in the other room, to pretend to be working late. There was no one, any longer, whom I needed to fool. Whose trust I would be betraying, who would be disappointed. Nothing I had left to transgress. Nothing that hadn’t already been washed away, signed over, or disavowed.