The key to her sultriness was her slowness, and the key to her slowness was her sadness — but when she was Lucinda la Miel, she forgot about all that. She gazed at the men in her audience as if she was intimately acquainted with each and every one of them. She oozed across the stage, slow as honey, one thick thigh thrusting through the slit in her gown, spine pulsing with an earthworm’s mysterious, self-sustaining grace, the meat of her hips pleasantly sore, the web of muscles in her abdomen rippling against the velvet. Most of the men out there were broke, tired, downtrodden, angry, hungry, but when she took the stage and molted — slowly peeling off her clothes — they were her babies. Their eyes dewed up at her with innocent devotion. She took that devotion and fed herself with it, drinking up all the power in the house.

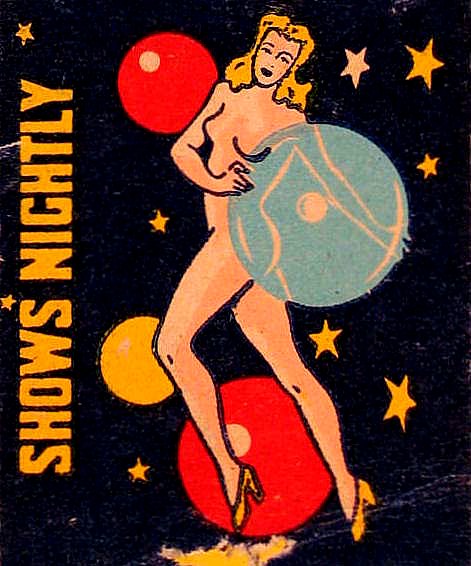

Vintage Graphic — Credit: Isabella Santos Pilot via Flickr

But out here in the endless plains of No Man’s Land, under a dull, constipated white sky, she couldn’t be Lucinda la Miel. She was Charlene James Turner — a tall, horsey bookworm with sandy, exotic eyes and a tendency to break into spontaneous shivers. A girl who married an Ivy League educated suitcase farmer at 18, and after he abandoned her in a fancy Chicago psych ward and took away their baby boy, turned to burlesque to survive. Charlene’s mother was buried five years now, and she hoped her father was still alive, but she hadn’t heard from him since the phone lines went down. So here she was, back in Caliber County, walking the long gravel road home.

The heat wave was finally broken, and the air was cool, but still. The flat plains of Charlene’s childhood were contoured now, morphed into a strange new dunescape, dust piled up in mounds against the fences, so that cattle would have been able to walk right over them, if all the cattle hadn’t been slaughtered. It was August 7th and all the fields were brown, stubbled with failed crops, acres and acres of dirt. “Dirt’s a bad word,” her dad would say, “call it soil.” But dirt was all that was left, as far as she could see. When they plowed up the buffalo grass to make way for wheat, they killed the roots, roots that were longer than she was tall, roots that stored moisture from years of snow. With no rain and no roots to hold it down, the soil was dead, the dirt loose and free to blow. But there’d been no black blizzards in over a week now, and to hear folks in town tell it, this whole mess just might be over. They were planting seeds, planning picnics, staring up at the sky, murmuring, “If it rains…” — “When it rains…” But it hadn’t rained, really rained, in almost three years.

Will skipped a breath when he opened the door and saw his daughter. He reeled in place a moment and bent over to push out a good chuckle, as if his excitement was light as helium and just might carry him off. His hazel eyes were still beautiful, but the skin around them was crinkled and dull. His shirt seam was coming undone at the armpit, and he had on a pair of leather gloves. When Lucinda heard him utter her real name — “Charlene!” — she melted into him, though his voice sounded different, like the voice of an old smoker. He smelled like dust.

“Dang my wildcats, that’s a drop. Feels like October out there,” Will said. “Ooh, let’s get inside, darling.” He took off his gloves and hung them from his ass pocket. “Ohhh! My darling…” He kissed her hand hard and led her inside.

“Where’d you come from? You must be hungry. I’m embarrassed, all I got to offer you’s hardtack and thistle — I was working on the spines, just now.” He tossed his gloves on the table next to a pan of cemented flour and water, a half-spiked green stalk and a knife. “She don’t make it easy.”

“No thanks.”

“Well sit down, then. Sit right here, you’re the guest of honor.” He patted the old recliner that he’d built himself, and announced that he and only he would sit in, when she was a child. She would perch in it anyway, just to tease him, to see if she could bring on a swat with his newspaper and a chase around the room. They were flush, in those wet teens and twenties, feeding Europe through the war, their wheat good as gold, lifting them out of the dugout where they ironed the walls at night to kill centipedes scratching in the sod. They built themselves this big, proud house, or at least it felt big and proud till she fell for a banker’s son who’d come out to Kansas to plant a crop, as if planting was some kind of hobby.

“Wait, honey, don’t sit yet.” Will pulled a handkerchief from his pocket and brushed the recliner down. “All I gotta do is breathe, I feel like, and I stir up the dust. I cleaned real good after the last storm, but I’d go crazy if I tried to get it all.”

The entire house was dulled by a fine layer of dirt. Grit gathered in the corners of the floors, and last year’s calendar hung on the wall. In December 1932, she was ripe and round, with a happy little creature swimming safely inside her, sure that his birth would bring John down to earth and save their marriage.

“I’m gonna ask you one thing… Did you hurt that baby?”

“Where’s Anthony?” asked her father.

“Boston.”

“Well. What’s going on?”

“I went there.”

“And?”

“They didn’t let me in.”

“What do you mean they didn’t let you in? If they don’t let you in, you insist, that’s your child.”

Charlene pulled an afghan over her lap. She bowed her head and squeezed the bridge of her nose. The house was dim, with the electricity cut off and the sky so drab, but she could see the stain where she’d melted the rug with an iron when she was twelve. Will got up from the couch and stood over her.

“That’s your child, god damn it. I don’t care what John did to you or what you did to John, that’s your child, why didn’t you insist? You just walked away? From your baby?”

Charlene’s face stung. Her chest collapsed and her ribs poked her heart as her father stood glaring down on her. He never yelled. The day she left the iron on the rug, he’d shrugged and smirked, “Why don’t you just iron the whole rug now, even it out.” And he never said god damn it, either: in fact, the one time he heard her say it, he snapped at her. “But you don’t believe in God,” she’d said, and he said, “I don’t believe in damnation either. But some words, they’re just bad luck.”

Will sat down on top of the coffee table next to the recliner. His voice dropped to a low breeze. “You look different,” he said.

Back when she was still in that big polished house in Chicago with the baby, the maid and the nanny and her mother-in-law and John — when John bothered to come home — she’d called her father from the bed where she was sweating shadows of herself into the sheets and told him she’d had some female troubles, birth complications, and wouldn’t be able to have more children. That was all Will knew about that. The plan was to move back to Boston, John’s hometown, once the baby was a few weeks old — the bank had almost collapsed, they had to consolidate — but then one morning Charlene lost control of herself, or so they said, and John and his mother took the baby and left without her.

“I look different how?” she said. Her voice felt deeper, deepened by her rage at Susan and John, or maybe it was Lucinda la Miel coming through — Lost Queen of the Amazons!, as her show poster said.

Her father just stared at her. Older, maybe he was thinking. She was 21 and already she’d been through the change. Worried. Tired. Ugly. Lucinda la Miel managed to be sexy — that was easy enough, she had hips and tits and a big rattling case full of stage makeup — but she was done being pretty.

“Hard,” he said. “You look hard.” He reached out and squeezed her knee. “I’m so glad to see you, baby, but you need to get out of here, there’s nothing for you here. You get on that train and go back to Boston.”

“They called the cops on me, Dad.”

“What, d’you punch John out again?”

“No! I didn’t even see John. It’s like a fortress, this huge house. Well, Susan’s house. I couldn’t find the new listing for John, though I know he’s right around the corner somewhere. The maid told me they didn’t want to see me. I wasn’t gonna push her down and barge in, so I just sat on the steps. I figured I’d wait for someone to leave, or someone to come home. But then the cops came.”

“And?”

“And they told me to go away, or they’d take me to the station.”

“Well, that was your chance!”

“So I got on a train and went back to Chicago.”

“Charlene, you’re crazy! You could’ve explained yourself at the station. You could’ve gotten the law on your side, you could’ve — ” A little dread rippled through Will’s body.

“I’m gonna ask you one thing,” he said. “I hate to ask it. But I have to ask. Charlene? Did you hurt that baby?”

“No!”

“I’m sorry.” His hazel eyes were muddy in the shadows of that middle part of the afternoon when time groans and nothing wants doing. “I’m sorry I asked. I knew the answer.” It wouldn’t be long before he’d have to light the oil lamp. He glanced up through the window at the colorless sky. The windmill was rolling in smooth, steady circles.

“I never liked your mother-in-law. And you know I like all kinds of people. Still. I can’t wrap my head around it. I can’t understand how someone could be so evil.” Will’s voice quavered like he was going to cry, but his face stayed dry. His skin was covered in a fine layer of dust.

“I broke some things in the nursery,” she said.

“Yeah, you told me. That was a mistake.”

“John had a black eye.”

“Well, that you took too far,” said her father. “You’re too damn wild sometimes, he never raised a hand to you—”

“He abandoned me. He moved into a guest room, he barely spoke to me, it was like he was married to his mother…”

“Well, I should’ve known better than to give my blessing to someone like him. Him and his big words and his pretty hands… But you shoulda known better than to beat him up — ”

“I didn’t beat him up — ”

“Now listen.” He reached out to pat her leg. A tiny blue light shot out from the yarn of the afghan on her lap and zapped his finger, but he seemed not to feel it at all. “You’re getting on a train tomorrow and you’re going back to Boston. You’re gonna wear something nice and ladylike,” he said, glancing down at her trousers, “and you’re gonna go to the police station first and get them on your side, and then you’ll go get Anthony back.”

“And then what? You think John’ll take me back? I embarrassed the hell out of him, with that black eye, I bet—”

“Forget John. Raise the boy yourself. Your mother never knew her father, and she turned out great.”

“But who’ll take care of him while I work?”

“Well, John should support you, that’s no sweat off his ass. He’s loaded. But if he doesn’t come to his senses… we’ll find a lawyer—”

“I can’t afford—”

“And in the meantime, hell, I’ll take care of him. I’ll be his nanny!” Will laughed, but it came out as a cough. “What else have I got.” He shrugged towards the spiny plant and the cemented imitation of bread on the table. “Can’t farm. I can leave here a while, till the rain comes back, and we’ll go to Boston, Chicago, wherever. You’re smart. You’ll find a job, and you can still be with your boy in the evenings—”

“I work evenings.”

“You got something already? Oh! You’re so sharp,” Will smiled. “What’d you find?”

“It’s in show business.”

“Whoo wee. Singin’?”

“Dancing.”

“I knew you had a performer in you. You were always dancing in the fields. Well, there you go, you’ll work hard, make it big, and hire the best lawyers there are. It’ll be all over the papers when you win, Charlene James Reunites with Kidnapped Child… Oh. Right. You’re still Charlene Turner?”

Charlene recognized the lavender socks on her father’s feet. They belonged to her mother. They were black on the bottom now, stained with dust. He looked wild. His hair was growing out, he hadn’t had it cut in a while, the part down the side was gone with all the static pulling his hair up, half sandy, half gray, fine as a baby’s, reaching towards the ceiling. It seemed to crackle ever so faintly, or maybe that was the crackle she felt on her own head. The charge in the air was growing, like the earth needed a good sneeze. She reached her arms under the afghan and hugged her knees in close to her body, and the hairs on her arms zapped up and strained towards the blanket.

“Oh.” Will scooted back on the coffee table and crossed his arms. “Oh. You’re that kind of dancer. Aren’t you.”

Charlene didn’t need to nod. Will made a slop-dumping, manure-shoveling face.

“A peeler,” he said.

She looked down at the black zigzags of the old gray afghan. She’d always found it ugly, but it did a swell job of hiding dust. When she looked up, Will was staring into space as if she’d told him she was dying. She’d seen the same grief on his face when he caught a glimpse of her first bra strap. She’d seen it when she wore a new dress and lipstick to a dance on a gorgeous June night, back when Caliber got rain and the air smelled of freshly threshed wheat. The first time her father saw John put his hand on Charlene’s waist, not long after he proposed, his face had that grief too — sweet, starry, hopeful grief, but still grief. Was it because her becoming a woman put him closer to death, or because it put men and their primal desires closer to her? If it was the latter, it must get him right under his skin. He was a man, too.

“You could do better,” Will murmured.

“I could,” she said. “But I can’t.”

His eyes left her and searched the cracks of his hands. They were stained with dirt. He got up and walked into the kitchen, and Charlene said after him, “The shops didn’t want me. Factories won’t hire women anymore. Everyone’s doing their own washing now… I asked for a job at the library, they just about laughed at me—”

“You could do better,” he said again. He handed her a photograph, and a blue bolt shot from his skin to hers as she took it. It was a baby, melting sideways into a bed, brow wrinkled, mouth pursed in a little o, gazing beyond the camera towards some thing, some idea, some nothing far out of sight. It was the photo from Anthony’s birth announcement. She didn’t have a copy. When John and his mother left, they left her with two bags of her clothes, and only the dowdiest clothes — wool skirts, blouses, plain white panties, a navy cardigan and some white Easter gloves that Susan had given her — if only Susan could see Lucinda la Miel flipping men inside out, nipping at those long gloves and pulling them off with her teeth. None of her books were in the bags, and none of her photos.

“Here she comes, fellas,” Max Balsa barked ten times a day, “And when she comes, you’ll think you died and went to the land of milk! and honey… presenting… Lucinda la Miel!”

The baby in the picture didn’t even look like her. She used to swoon at babies back when she was in love with John, but now babies seemed like pets, more or less, no different than poodles, just a lot more work and a lot more eyes watching and waiting to tell you what you were doing wrong. Maybe she’d get that warmth back, though, if she saw him again. He was eight weeks old, when they parted, just starting to smile, to grin his pink, gummy grin and wiggle in excitement whenever she walked into the room.

“This is your baby,” said Will. “You have a baby. Do you hear me? Do you have any sense left in that head of yours, or am I just talking to the dust.”

As she looked up from the picture, he slapped her cheek. The static backed him up and doubled the sting. He had never slapped her before. He’d never even spanked her.

“You have a baby, and your baby’s been stolen because of a mistake that you made, and you’re dilly dallying around Chicago, throwing your clothes at strangers? I mean, you’re telling me you gave my grandson up to that high-bred bitch so you could go off and squander your smarts as a whore?”

Charlene stood up. The afghan fell to her ankles, and sparks zipped around them. She was so cold without it. It did feel like autumn. Her father stood in front of her trying to tie her up with his eyes, that slap still slapping, the sting of it seeping deeper into her face.

There. She’d done it. Her mission was accomplished, and she’d accomplished it quickly. She knew now that her father was alive, which was all she had set out to know. She supposed she’d thought he could help her in some way, too, but clearly that wouldn’t happen. He could barely take care of himself.

The Spark Theater in Chicago shut down for the summer, and she’d spent the last two months traveling all over middle America with the Carnival of Wow, dancing in the cooch tent — The Oasis of Delights. “Here she comes, fellas,” Max Balsa barked ten times a day, “And when she comes, you’ll think you died and went to the land of milk! and honey… presenting… Lucinda la Miel!” If she left now she could catch up with the Wow by tomorrow, or tonight if she was lucky, she’d barely miss any pay, and all that money would be plenty to get back to Boston when she was good and ready, to rent a nice hotel room and everything.

A new voice, charged by the electricity in the atmosphere, rose up through her. It was softer than Charlene’s voice, and far softer than Lucinda la Miel’s, but there was something of Lucinda’s faith in it. It told her that whatever instinct carried her away would do so for a good reason — but it couldn’t show her the reason until she was well on her way.

“Okay, Dad. I’m sorry. I better go get him now. Right away.” She went to the door, grabbed her bag, and dug to the bottom for a sweater.

“Don’t be a moron, there’s a duster coming. You get back in here and sit down. I’ll take you to the station tomorrow.”

As she pulled the sweater over her head with a crackle, his eyes took in all of her, the way men’s eyes did when they were calculating what they might be able to get from you. She should have been sharp enough to lie. Why hadn’t she lied? He’d seen her naked in his mind now, naked on stage, and there was no way to erase that. Her mother was the one with the famous mouth, not him, but even Rose would never say a word like whore. She didn’t want to be stuck in a storm by the light of an oil lamp with this man looking at her the way he was looking now, blood relation or not, lavender socks or no.

Will grabbed her waist. Her bag bumped her thigh as he tried to steer her back towards the recliner. “Sit down,” he ordered. “You don’t know what these new dusters can do, they’re not like any duster you ever saw—”

She swatted his arms, caught them and squeezed them at the wrists. They’d gotten bony, though his forearms were as soft with fuzz as she remembered them. The fuzz crackled with static, reached out and tickled her flesh as his hands dangled in surrender. She gripped him hard. His eyes churned with terror.

“No, I need to go now,” she said. “There’s no time to lose. I’ll be fine.” She dropped her father’s arms and burst out the door.

The air was so cold, it felt like she’d been indoors for months. There was no storm in sight. The sky was dull and white as an old toilet. Charlene looked down at the rock hard earth under her feet and tried to imagine how much rain it would take to fill the cracks and soften it up. But the dunes were plenty soft. She would have been thrilled to climb them as a kid. They were textured with graceful ripples, painted by the wind, just as the sand of Lake Michigan was shaped by the waves.

“Charlene, I’m sorry,” her father said from the porch, but she was already halfway down the driveway to the road. “I’m sorry I said that, I know it’s not easy to get work…”

A big dune lay up against one side of the house. That was why it seemed so dark inside: it covered the windows on that side completely. Her dad could have gone to the effort of digging the house out and putting a little light back in his life. He sure wasn’t busy with farming anymore. One dune had a rearview mirror poking out of it — the car. Like hell he’d be able to take her to the station, it looked like he was content to stay right here and rot, in his dead wife’s lavender socks.

“Come on, baby. You come back now.”

Charlene watched him as she walked slowly backwards towards the gravel road. It was two miles to the main road, then a couple more to the station. If it did storm, and she didn’t beat it, someone would come along sooner or later. She could hitch a ride.

“I said I’m sorry and I mean it, now don’t let your anger get the better of you.” Will’s voice had a withered scrape to it. He’d gotten old in the three years since she left home. His tall, lean frame looked crooked against the column of the porch. A long mess of rope was tied to the column, and Charlene couldn’t decide if he looked more like a child with some silly climbing scheme, or an old man who’d gone off his rocker and decided to decorate the house with junk.

“Please!” he shouted into the breeze. “Folks have gotten killed in this.” The windmill was still rolling along, content as could be. It wasn’t bad out here at all.

Charlene walked faster, still backwards, eyes fixed on her father to determine how badly he really wanted her to come back. If he wasn’t running after her, it couldn’t be that bad.

“Then go to the Walters’ if you’re so mad, go wait it out there, but hurry, so you get there in time.”

She turned her back on him and set off down the road into the new dunescape, to start fresh under this blank, wide-open sky. The force that had brought her here was already carrying her back to the Wow, and right on time. It was a mysterious engine, like the wind. Perhaps the wind would inspire her next performance. Isadora Duncan might have done it already, but Lucinda la Miel should give it a whirl. She’d been dreaming up all kinds of future acts: a huntress Diana clad in shreds of animal fur, aiming invisible arrows of passion at the crowd; a strip inspired by Houdini, the curves of her body straining to break free of zigzagging metal chains; a Lady Liberty act, complete with a torch that would blaze to life the instant she dropped her robe to reveal her naked glory.

Susan, who showered morning and night, who dabbed her lips with a starched napkin after every bite, who noted the most relevant passages of Emily Post’s Etiquette with razor-sharp pencils…

An hour with her father and already her muscles seemed to wither, but now they flushed with blood as they thrust her forward, towards the horizon of endless possibilities. That was one thing the plains had on the city — infinite space. But the city was infinite with stories, a labyrinth of curiosities, with a healthy tolerance for the odd and the eccentric, which was more than she could say for the Walters, who lived a mile up the road. Like hell she wanted to try and make up a story about her life that would not shock and offend Maureen while Maureen sat embroidering another family tree with holy scripture floating in the sky above. She didn’t understand how people like the Walters didn’t implode from the force of their own dullness.

The wind blew towards her — steady, efficient, not a wind of vengeance but the long, contented sigh of some great spirit, washing all the hardness and ugly out of her face, massaging those tiny muscles she didn’t realize she’d been holding so tight. The wind blew her so clean, her face took on the magnanimous emptiness of a god.

A little blue crackle of static skipped along a wire fence, coaxing out a shiver — her trademark. When people said, that gives me chills, or it sends a shiver up my spine, they seemed to be referring to rare events, but she felt those tingles all the time. Back in school, kids had laughed at her, said she was touched, or had a case of nerves, and she learned to keep it under control. But now, when she let it happen on stage, she could melt the crowd. That quivering that got her called a freak ended up paying her room and board.

The tingles swarmed her chest. Her nipples were waking up. Their whole galaxy of glands, and sensations, and desires, had been smothered by the nurses who bound her breasts with elastic to stop up her milk this winter, murmuring about how nutritious formula was, how it was the choice of every woman who could afford it. Then she’d plugged up her nipples all spring and summer, with the pasties and their awful adhesive.

She turned back. Her father wasn’t following, but he was watching. He just stood there, holding on to the banister, looking feebly on. Tumbleweeds bounced across a deserted field to the south, and a light dust swirled up from the ground, like steam from a cup of tea. John’s land was just beyond that field, but like all the hobby farmers, he abandoned it when the drought hit in ’31 — the year after he married her. He called her his Venus, his exotic, tiger-eyed beauty, flooded her spending account so she could fill their library with books, defied his mother and his dead father’s honor to marry her — “Deciding to marry you is the only thing I’ve ever done that I really wanted to do,” he said. “Everything else, I did because I was supposed to, because it was already laid out for me, because it made her happy, or him happy… But you’re the real thing, Charlene. You’re the real thing.” And then he left her after all.

Another light zipped down the fence and she shivered again — just being near it gave her the same pleasing jolt she used to get from licking a battery. But the static kept crackling along, and another blue zig zag zapped to life, and another. They started to grate her nerves, as if they were trying to reach right through her skin, trying to ignite her, just to see how she’d explode.

Her mother-in-law should have understood how she felt after the hysterectomy. Surely Susan had already been through the change, but the woman had no ability whatsoever to put herself inside another’s skin. Neither did John. Charlene showed him her soaked sheets — two sets in one night — and tried to describe the blazing in her blood, the sensation of fire ants charging her brain, but he just said, “Well, I shouldn’t disturb you, you need lots of rest. I’ll have Vivian buy some more sheets so we have plenty on hand.” Then he walked out of the room like she was contagious.

It couldn’t be past four o’clock, but already the plains were getting dark. The sky was the color of sand. It didn’t look like daytime anymore, but it looked nothing like night. It was no man’s time.

That day they sent her away had started in no man’s time. It was early, just before dawn, and Charlene was rocking with Anthony in his room, a nightlight glowing at her feet. After a long night in her bed with no sleep, she’d come into the baby’s room and finally drifted off with him in her arms, letting him suckle at her empty breast, rocking back and forth to the depths of his contented breaths. In the dregs of the dark, little dream shreds rolled in and out, in perfect synchrony with the waves of the lake just outside their home. Then a creak chopped the waves. The door. She opened her eyes to see her mother-in-law standing in the dark, in her ruffled, neck-choking nightgown.

“Oh dear God. John! Come quick, she’s gone mad! You let that baby go right now, you don’t have any milk. Are you insane? Are you using my grandson for some sick, perverse… I can’t… John, I need you!”

Susan snatched Anthony out of Charlene’s arms and held him upright against her chest. She patted him furiously, and he began to wail.

Charlene pulled up her nightgown and screamed, “He doesn’t want you! What are you holding him for now, you never hold him, you told me it’d spoil him to hold him, you just want him around for decoration.”

Her mother-in-law’s face crumpled in righteous shock, and she bounced the baby to an ugly, jagged rhythm while he wailed loud enough to throttle Charlene’s steaming, sleep-starved brain. She grabbed a ceramic figurine of a dopey-faced duckling that Susan had bought and hurled it to the floor. A crystal angel and a toddler kneeling in prayer followed. The toddler merely cracked, but the angel shattered in glorious pieces.

“Good God, John, come now, she’s dangerous!” Susan was right by the door, but she planted herself against the wall like this was the spectacle she’d been waiting for, ever since her son had shocked the family with his sudden marriage to this sullen, big-boned farm girl of questionable ancestry. She bounced her grandson so fast it hurt to watch it, her hand wrapped around his head, while he cried and cried and cried.

“Not once have I ever seen you play with him, or smile at him, or feed him his bottle,” Charlene spat. “Did you ever feed John? Did you ever once feed your own son?” The words scorched her throat on the way out, but better that than burning her alive. “Did you ever change your son’s diapers, and wipe his ass — ”

“You’re a danger to this family.” Susan’s voice quavered. “You have a sick mind.” The baby wailed harder and she said, “I knew it the day I met you. I tried to warn John, but he wouldn’t listen…”

A hint of purple was creeping into the room, through curtains which had arrived in the post all the way from the UK, courtesy of Susan. Charlene had plans to sew curtains herself — pregnancy gave her a new, woozy enthusiasm for womanly arts — but Susan had beat her to it. John agreed with his mother that the fabric Charlene picked out looked a bit cheap, more flammable, and nodded absently when Susan declared that her curtains would remind baby that his daddy had a year lived in London. In the dawn light, their pattern sharpened: redundant arrangements of cheery children in petticoats and sailor suits, wooing royal guardsmen to lean over and greet them, riding double decker carriages, swarming in droves up ladders to bother elephants. Charlene hated them. She grabbed ahold of them and ripped them down so hard that the mounting rod burst free from the wall with a little chunk of plaster, and white dust rained on the rug.

“What took you so long, I needed you!” said Susan.

Charlene looked up from the rumple of happy children she’d pulled to the ground to see Susan putting the baby down on his back on the changing table, and throwing herself into her son’s arms.

“See?” she blurted into John’s chest. “Now, will you finally open your eyes and see how wild she is?”

Susan, who showered morning and night, who dabbed her lips with a starched napkin after every bite, who noted the most relevant passages of Emily Post’s Etiquette with razor-sharp pencils in a little leather-bound journal because dog earing the pages of a book would be wrong, who sketched out holiday table settings right down to where the salt and pepper shakers should go, and made her maids rehearse it days before the dinner, was now sobbing into John’s chest, quivering and jiggling like a Jell-o dome. Her loss of control would have given Charlene a thrill, if Charlene weren’t so dizzy from the fury dawning on John’s face.

Anthony lay screaming and kicking the empty air. He’d been so content snuggled against her just moments before. Susan clung to John’s neck like a wife or a little girl, sniffling up at her son, “She’s sick! She was using the baby, I saw it, she had him on her — she was trying to…”

John pulled his mother’s arms off his neck and came at Charlene, kicking aside a piece of the duck on the way. His face screwed up tighter and more crooked than any impending orgasm, any bad deal at the bank, or any of Charlene’s refusals to smile and make chitchat at this or that function, luncheon, or gala had ever tightened it. His face was ugly. It was scared.

“What is wrong with you?” he said, and he grabbed her by the shoulders and shook her. As her head flailed, both her arms shot out at once. Her fists hit his face and they hit each other at the same time, so that her inner knuckles flamed in pain.

A trickle of blood moseyed out of John’s nose, paused on his upper lip, then dripped into his wide open mouth. Susan dashed towards him, but she tripped over that piece of ceramic duck, and fell flat on her stomach on the rug.

The baby stopped crying. No one said a word. Susan lay on the floor, a shocked Sphinx, forearms propped up on the rug. She stared up, open-mouthed, at her son. John glared at his wife, glared down at his mother, and glared back up at Charlene again. Her hands were aching. She gazed down to watch them bloom open, from fist to trembling claws.

The baby eked out a few odd sounds: “Geh. Ehh… Uhh? Ehhhhh!” His arms and legs rose up and waved in synchrony, doing a backstroke in the ocean of change that had just rolled over the room. The purple dawn was over, and a new gray day hit John’s face as it morphed from bad to worse: fright, then rage, then, a plan. They sent her to the nicest psych ward in town, so nice it felt more like a hotel, and she was discharged in less than a week, but by that time, her baby was already a thousand miles away.

She had never breastfed him. Formula had more vitamins, the doctors insisted, and in a rare spark of warmth, Susan had leaned in and said, “It’ll help you keep your figure, too!” But after the hysterectomy, those nights that Charlene was up clawing the sheets, dreaming while awake of termites scratching out tunnels in her chest, the least she could do was feel useful when the baby cried out. The bottle wasn’t a surefire fix, Anthony didn’t always want it, and what he wanted that night was company. Susan always warned against too much holding, and the author of The Psychological Care of Infant and Child confirmed that it would indeed spoil a child — but Susan was in bed.

“Shhh. What do you need, baby? You got it all! Shhh….” The rocking cooled Charlene’s head, lulling the termites and the fire ants to sleep. Maybe, after a long night of thrashing in her bed, it would finally put her to sleep. And if the rocking didn’t put her to sleep, Anthony’s soft sweet hair might do the trick — it smelled intoxicating. He let out a tiny grunt, sucked the heel of her hand, turned and wetted her chest. She pulled her nightgown down and he went straight for her breast, like that was what he’d been asking for all along — the closest closeness, the assurance that he came from somewhere, that she wanted him, that she wasn’t the one who’d decided to vacuum him out with that new patented birth acceleration device that just about pulled her uterus out with him, so that she’d had to go back two weeks later to have it removed. His skin against her skin gave the heat in her blood a reason to exist. Her tits tingled, termites turning to butterflies, as he sank into her at just the right angle, the rocking chair creaking to the rhythm of his pink suckling lips, and the two of them dozed off on the same drift.

Was that so wrong? Was it really so terrible, to comfort a child that way? It wasn’t the first time she’d done it. It was the third or fourth. Was it more for herself than for him, and if it was, did that make her sick? She’d had a little hope that milk would start to flow, but her nipples, like the rest of her, were dry as dust. Would her father understand, if she told him? Or would he just lock her up again in that stare of terror?

Charlene heard a flock of birds flapping over her head. She’d been standing here in the road with her eyes closed ever since that blue static on the wire fence had jolted her and her breasts back to that morning. She hadn’t gotten far at all. The birds flew in spurts and scrambles, almost crashing into one another as they made towards, then beyond, her father’s farm. He wasn’t outside anymore, at least not that she could see.

When she turned forward again, she saw the black mountain coming. She couldn’t hear it. There was barely a sound in the air, aside from the hum of the wire fence. The wind didn’t even have much to say. It just rippled the hems of her trousers, seeming to murmur that all would be okay.

Aside from the birds, who were already gone, the moving mountain of dust was the only sign that these plains were still alive. It was miles and miles away. She still had time to go back home, it seemed, probably even had time to run to the Walters’ up the road, but it looked so fantastic, rising higher and higher against the flatlands. It roiled like a tornado on its side, like a triumph from hell, like Demeter herself wreaking new havoc on the earth, so that maybe, finally, someone would wake up and pay attention to the evils that had been wrought.

“I did this,” she said out loud, and like that, the electricity that had zapped her nerves found a circuit. It coursed freely through her blood now, buzzing through her entire body and beyond, so that she felt larger than ever, larger than she’d felt even during her finest performances. “I’m the storm,” she whispered. Her child had been stolen, and just as Demeter made the earth barren when Persephone was kidnapped, hell would rise up to rain down on the plains till Charlene got Anthony back.

“You did this,” she said. Her parents did it. John did it. All the fools in Caliber County did it, trying to make something of No Man’s Land, ignoring the old folks’ warnings of cycles of drought, denying the foreboding monotony of a land the Indians knew was only good for wandering. They slaughtered the Indians and the buffalo and lured out poor people like her parents with free train tickets, taught them to plow up the soil too deep and too fast, to plant so much wheat, it would glut the market and rot. They ripped out fields of wildflowers that fed the bees and gave them the golden honey that she and her mother used to harvest. Honey, miel: she’d pulled a French dictionary off a library shelf to find her stage name.

“You killed the land. But I make it blow,” said Lucinda la Miel. The wind picked up a few locks of her long hair and tossed them around in confirmation, blowing a graceful yes onto her face. Her lips tasted stale. She’d already acquired a fine layer of dust over her body, just like her father, fine as pollen, so fine she hadn’t noticed it sneaking up on her. She licked her fingertip and wiped her cheek. It was black.

The dirt was dead, but the mountain moving the dirt towards her was most definitely alive, and growing fast. It forced the world around it into night, blowing plans up, ridiculing civilization, compelling people to huddle inside and give thanks if they were still able to breathe, but Lucinda would not be afraid. If she could make it through this, she could make it through anything. It might just be the last layer of hell she had to go through to get her baby back.

We must go deeper, into greater pain — Art the human radio said it this morning. He was the stagehand for the cooch show, the eunuch of the harem, as Madame Zola called him, a gawky, meticulous man who kept his head down, worked for cheap, and could barely speak unless he was echoing a movie or a radio show — “You don’t leave here without having fun!” — “With Goodyear, you’re in good hands…” The girls were safe with Art, Zola insisted — he couldn’t stand human touch and it hurt him even to look at people — but Lucinda had caught him petting her clothes as he folded them, inhaling her skirt with the passion of a street kid huffing glue. And then, this morning at dawn, when she left the carnival in Plainview to go find her father, Art hung a pair of aviator goggles and a paper mask on her wrist. It was the protective gear he wore when he cleaned the outhouses. His nostrils twitched as he gazed beyond her into the purple sky, opened his mouth and let out the voice of an actor on some evening theatre program: “But the stars that mark our starting fall away. We must go deeper into greater pain, for it is not permitted that we stay.” She tried to refuse his offer — “No, weather’s fine now, they said so on the radio, the dusters let up” — but he insisted. He was a freak, he was touched, and yet he knew things other people didn’t, like animals who sense distant storms trembling in their blood.

So here she was going deeper into greater pain, and if it killed her, well, why fight fate. Her nipples tingled again, though this time with a cold, deep ache, and her belly cramped as if she was still in her old body and that time was coming on: the time in her cycle that compelled her to slow down and just be.

As the sky of the new landscape got darker and darker, she stood between two worlds, a dark world and a light world, the true world, and the delusion. Could this storm blow far enough to wipe out the Carnival of Wow? If she made it through this, she’d have no need for the Wow. Her dad was right, she should go to Boston for her baby as soon as she could.

She dropped to her knees. The dry, compacted dirt hurt. If she was really so sick and wrong and wild that she couldn’t be forgiven, well, now she would find out. The storm would be the judge.

“Forgive me,” she whispered, but she couldn’t hear herself. The wind blew so hard she had to put down her hands to steady herself, standing on all fours like a dog. Dust swirled up from the earth, bounced down and picked up more dust, dust magnetized to dust, the ashes of the dead soil gathering up their own electric intelligence to haunt the land. She could hardly see anything but dust. She reached towards her bag for Art’s goggles and mask, but then a roar gulped her up in blackness, steel wool scraping every inch of her body, and it was too late. Her bag was gone.

Her face took a million slaps, the ash blasting off the top layer of her skin as she ate mounds and mounds of dust. She tried to spit it out, but her saliva was gone, and coughing it out just made room for more. She couldn’t keep her mouth shut: the wind kept forcing dirt in. Her eyes blazed, and when she tried to cover them, she couldn’t even see her hands in front of her face.

She curled in on herself, forehead touching the ground. She was sure she’d look like a mutant when the storm was done, or a burn victim. Her career as a whore would be over, and now it was mother or bust. What a terrible thing, though, for a child — he’d get used to it eventually, but he’d have to watch strangers look at his mother like a monster for the rest of her life.

On the train she’d seen thousands of acres of wheat fields lying fallow, enough to fuel years and years of storms. Dad had to get out, or he’d choke to death, like she was doing right now, coughing and coughing, trying to hack up some saliva to ease the scrape of dust in her throat. It was sharp as a million tiny shards of glass. This had to be as bad as childbirth, though she wouldn’t know, since they’d given her the twilight sleep — painless, they promised, easy, the procedure chosen by every woman who was lucky enough to have a choice.

Already her muscles ached from curling into this ball, rocking back and forth like a boat in the storm, staying as small and heavy as she could so as not to be knocked down. The dryness she’d felt since going through the change had nothing on this. She was as dry as a corpse picked clean by the worms. The dust traveled up her nose and mouth all the way to her brain, where it would turn to mud and crust up the folds. It would turn her into an invalid, and then she’d spend the rest of her life laying on her father’s recliner, sucking on hardtack and thistle root, wearing her mother’s socks.

No job, no responsibilities, no guilt, no man trouble, no crying kid, a brainless, sexless existence: that didn’t sound so bad. Her father would brush her hair and trim her nails, and he’d entertain her, reciting the same three poems he knew by heart. Every time she heard a poem it would feel like the first time, or, if she was too far gone even for that, if she was the type of invalid to just stare at the ceiling and moan, her father would rub her feet instead, pat her head now and then and say, “Atta girl…. good girl, Charlene.”

She rose to all fours to turn back towards the house, but a gust knocked her over and banged her head on the ground. If these dusters could crack telephone poles in half, she had to be more careful. She aimed again towards the house — or where she thought the house might be — in this darkness she couldn’t be sure — and remembered her father’s army crawl. He never talked about the war in the Philippines, refused, in fact, to talk about it, but once in a while he’d fondly recall some bizarre and delicious tropical fruit, or show off a trick he’d learned.

Even with the wind at her back, it took all her might and more to crawl like this, but if she stood up, the wind might knock her down again. At least it was blowing at her ass now, instead of her face. No trains would run tonight, and no way could she face Lynn Walters in her doilied shrine to the Lord, with her husband Eric who always talked Charlene’s ear off about anything and nothing just to have an excuse to stare at her. Those weren’t the witnesses she wanted when she wiped the underworld off her skin to reveal the stinging punishment underneath. So she kept on crawling. If she did choke to death, she’d be that much closer to home, and her dad could just scoop her up and bury her right there. Her sweet dad. She shouldn’t have left. One more sin for the list: she’d made him worry.

Anthony was seven months old now: maybe he’d already learned to crawl. Mother and son might just be doing the same thing at this very moment, him on some ivory carpet in the clean Boston sunlight, her in utter darkness with the wind howling at her about what an idiot she was, if the wind even cared. She’d been just as superstitious as the Bible thumpers, believing that the earth cared what she did. The earth didn’t care at all. It would revive and grow lush again, after we rid it of our existence.

It was still as dark out here as it had been inside her mother’s womb. She hoped she could find the way home, but then, how could she, unless she bumped right into the house? Dirt was everywhere — lodged in the crevice between her breasts, in the cracks between her legs, and deep in her lungs, sharp as glass, making every breath itch and scratch. Her eyeballs burned. The wind was blistering her hands, scraping her skin, flogging her entire body, but it was just her mortal pea brain that told her the wind was angry. The wind didn’t care a whit. Somehow, though, indifference felt worse. She’d rather the wind be mad. But then it started calling her name.

Arr… eee…. arr… eee… The vowels burst through the whipping and wailing first, then the consonants drifted in to ground them. It was definitely her name. Could she convince John to have her locked up again, this time for illusions of grandeur? That had been one heck of a madhouse, nestled in a big fancy hospital, with room service and her own phonograph and radio set, and a view of Lincoln Park.

“Char…lene!”

When she opened her mouth to call back, she ate another fistful of dust, so she cupped her hand over her face and called through her fingers, “Dad!”

“Charlene!”

“Dad!”

“‘lene!…”

“Dad…”

She and the voice kept calling to each other in the dark, until her head bumped into a leg and a hard boot stepped on her fingers. The pain of that step was so good, it felt like a dream. It must have been a dream: there was no way anyone could stay on their feet in a wind like this. But then something grazed against her face with a tickle.

“Uhh…” struggled the voice through the howling, “…. up!”

She still couldn’t see him, but she reached out until she caught the rope and pulled herself up. Now she understood why it was tied to the house. Her body waved from side to side in the scrambled cross currents of the black blizzard. She squatted low to steady herself, then pulled hard and took a step like she was learning to walk for the first time.

Maybe she would be there on the day that Anthony stood up and walked across a room for the first time. She’d seen a baby take its first steps once, and it was such a feat. Getting the gait just right, the faith in the gait, and after a life of crawling, finally standing up on two feet to soar across the floor: that baby might as well have been walking on water.

“Pull!”

Hand over hand, she pulled herself forward on the rope in the dark. It sounded like an army of Demeters was on a rampage, troops of Lucinda la Miels, Charlene James Turners, Huntress Dianas and Lady Liberties howling, scratching, breaking every toy and every figurine, every pot and pan and medal and trophy and piece of fine porcelain on the planet, snapping tree trunks and smashing cars, banks, monuments and carnivals, stirring up hell, sucking the world dry. In the scraping, blowing whirl, she couldn’t see or hear her father at all. She couldn’t stand to call out again — her throat refused to eat another shard of dirt — so she stopped pulling, held the rope tight, and rode the wind. The rope jerked from side to side in her hands, but the anchor was the house, and the house was strong. Then Dad was there. He tripped against her back. “Owe! Ama, baby, ohhh!” he seemed to say into the woolly scramble. She squatted deeper and pulled harder, palms blazing against the rope, snakes of hair lashing at her face in the screaming dark, pulling hand over hand, over hand over hand, on the tether that would take her home.