Night.

Homecoming starts after sunset.

The crowd spills in from the three directions: East lot, North lot, and Weir lot — the one named after the teacher who died the year before we came. The bleachers fill quickly: parents in the middle, tiny freshmen in the front, juniors and sophomores on the right, and the seniors who still deign to come slouching in the back. As usual, the left remains empty. That’s where the smell comes from.

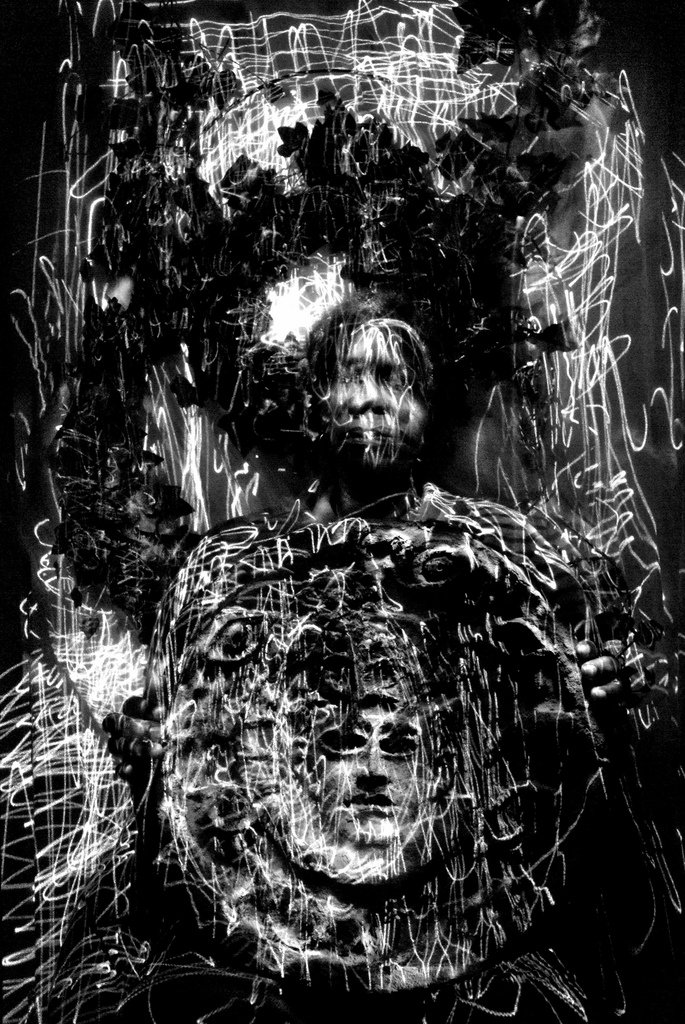

“2.21.12 No. 1,” photograph by Steven Erra

This is the first year we see the pattern from afar, from the field. Middle, front, right, back and then that odd left circle of emptiness, like a hole burnt in a blanket. Frank sat there once at the end of 8th grade, by accident, before any of us knew. The next year we were first years, that teacher was already dead, and we sat with the freshmen and forgot. This year I’ve got a trumpet and I’m on the field. The band smells like brass and snot because it’s cold and every one of us is allergic to something. Frank hugs his tuba and snuffles his big wet nose. He’s whispering, “There it is. There’s the hole.”

We’re all watching it.

There are theories, of course, about the smell. An old septic system, toxic waste, a dead body. They dig up the spot every spring after the thaw and every fall before the first game. There’s nothing there. Frank says it’s haunted by a poltergeist, a smelly one, or a den of walking dead. The sax is next to him, looking skeptical. No, he says, it’s a sacrificial site, or a vortex, or a curse.

Or a boy.

I’m not aware I’ve said it aloud until I notice everyone looking at me. I shrug and gaze at the ground, clicking my trumpet valves until they’ve forgotten it.

I stare at the grass bright green under the field lights, listen to the referee’s whistles and the cheerleaders’ cries. But all that’s in my mind is a quiet midnight, the snowy field behind our house, the long wooden fence crawling up it like a snake, and the Loana boy, dark as night, standing at the other end of it, his white eyes turned on me.

The family moved in the summer before 6th grade, into a little white house at the end of my street. There was a mother, a father, a boy and a girl. There was a dirty pond in the back yard that spit out toads. They were supposed to be from some place in Africa.

“Give what you don’t know a name. Then when it gets mixed up with things you do know, you can still keep an eye on it.”

We waited for those kids to show up at school, to get a good look, but they didn’t come until two Septembers later. I was staring at my math worksheet, the equations already starting to blur, when there was a sudden coolness next to me, like a puff of sea air, and I looked up to find the blackest boy I’d ever seen. Without thinking, I told him that. He laughed and said I was the whitest boy he’d ever seen so we were even. His voice was husky, deeper than any 8th grader’s should have been. His eyes dropped to my equations and then back up to me. He grinned the grin of understanding.

“That number’s not real,” he said, his long finger tapping my pencil scratches. “That’s your problem. You made an imaginary number by accident.”

I stared at my paper. Imaginary?

Our math teacher then was a serious old lady, boring but not unkind. She told the new boy he was in the wrong class. She sent him to the advanced class. To Mr. Weir.

I’d never seen the man, but I’d heard his voice, loud and nasal, coming out of his room and down the hall like an air raid siren.

I only saw the boy in the halls after that. Sometimes he would notice me and turn his head, his grin of understanding gone.

At lunch, or on the weekend, we came up with explanations: why the Loana kids didn’t make friends, why they were so smart. Secret agents. Aliens. Mutants. Frank, of course, said voodoo. Zombies. Frank has never understood “smart”.

At night, at the dinner table, they talked, too. Abuse, said my mother. Ghosts, said my little sister. Not surprisingly, my stepfather had a view similar to Frank’s. “That’s what they’ve got over there in Africa,” he’d say …a lot. “Those old fucked up religions. Be happy you were born here. With God.”

Each day I’d look for him, the boy who knew about the imaginary numbers. Who came from the place without God.

I found him once in the library by the windows, sitting against the sun.

“So, I can just make up numbers?” I asked. “I can pretend?”

He was a dark patch in that light, the eye whites tracing my face back and forth, trying to grasp me. “No. Not pretend. Just because it’s imaginary doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.”

He said they use them in the study of electricity, to predict the path of alternating currents. This made no spark in my damp brain, my math worksheet still plastered there. He tried again:

“Give what you don’t know a name. Then when it gets mixed up with things you do know, you can still keep an eye on it.”

I said nothing, my mouth open a bit.

“You see?” he smiled. “You’ll always recognize it by the things it is not.”

I left him then, to finish his homework. The word was Weir didn’t like him, that he’d called him a cheat.

Things my stepfather is not:

Smart.

Good-smelling.

My father.

That’s how I recognize him.

We could all hear it the day Loana left school for good, the air raid siren filling the halls.

Disrespect!

Cheat!

Animal!

What he is not, I thought. That is how Weir recognizes him.

I waited outside, that night, in the snow. The long fence was no longer a snake, but a current. Eventually, as the moon rose, the boy appeared at the other end of it. I crossed the field and stopped in front of him. I kept still, my sneakers filling with snow-melt, facing him squarely to show my allegiance. He shook his head like he didn’t want it.

At home, he said, we get rid of our hate at night under the moon.

Why?

You let Hate stay too long, it thinks it belongs to your family and won’t leave. It starts to smell bad. You have to leave it outside for the moon to watch over and keep in check.

He waited — the way he waited after a math problem for me to understand. I understood he was giving me advice. I understood when he said “home” he was not talking about a small white house. But that was it.

Two days later Weir was dead. A heart attack. “Predictable,” my elderly math teacher whispered to someone out in the hall, just past the threshold, “for someone with such a hot temper.”

Later, I waited by the fence, under the moon, but he did not come.

I waited each night until the moon shrank to nothing and there was no reason to wait anymore.

At lunch, on the weekends, we discussed it: the Loana boy, Weir, the heart attack. You couldn’t help but see the connection, even if teachers and guidance counselors did not.

At night, at the dinner table, my stepfather saw connections, too, and my mother crossed herself as he said them out loud. I watched him, quietly over my fork, waiting for his hot temper to do something predictable.

I watched them the day they left, in March, so early in the morning there was barely a sun. I stood by the tree in our front yard, bare feet in the mud, running my knuckles up and down the bark. I watched him help his little sister carry her suitcase down the porch steps.

They had only enough to fill up a minivan. I’d only been watching for twenty-two minutes before they were done and drove off and my hand started to bleed.

When he found out the white house at the end of the street was empty my stepfather said, “Good.”

My mother was pregnant again. She took my hand and put it on her belly before I could pull it away. My sister said it felt warm. She was right.

I stopped going home. I stayed at school until they told me to leave. I trekked to the high school and sat in the bleachers, an eye sometimes on the football practice, sometimes on the sky. When the right day came I hid until the last coach had gone, glancing over his shoulder at the bleachers, not seeing where I crouched below, waiting for night.

I left it all there.

The moon keeps its promise, though.

From within our brass huddle on the field, beyond the lights, the crowds and their stomping feet, I see it in the dark between the metal benches, the thing with the whites of my eyes and my hate, standing beneath. When the hole appears, with its stink of something left to rot, I feel a quiet satisfaction.

I can recognize this thing for what it is not:

A poor math student.

A new half-brother.

A boy.