On April 23, 2011, during what is known in Mexico as Semana Santa — or “Holy Week” — I went swimming off of the coast of an abandoned beach at the edge of the northernmost jungle in the Americas, Los Tuxtlas, and a rip current sucked me out to sea.

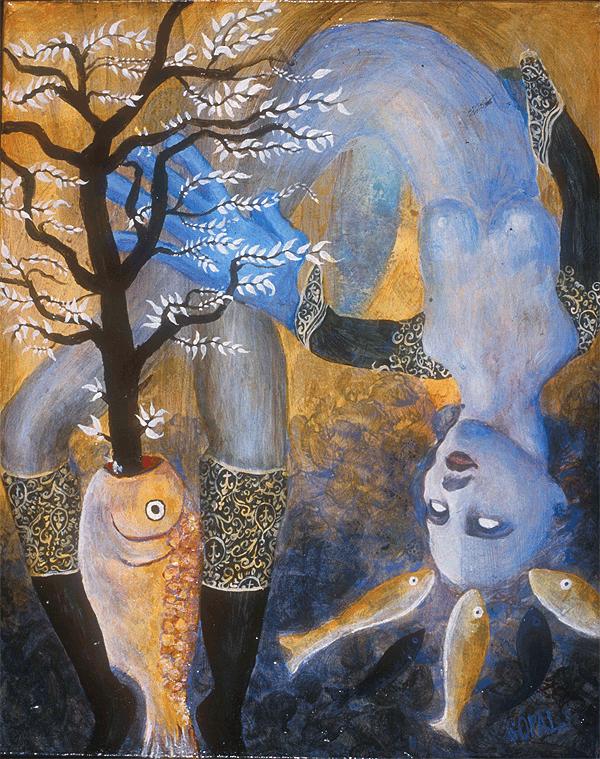

Fisherwoman (2000)

by Carl Gopal

Four other foreigners and I were the only people on the beach; we were a 20-minute hike from our rental vehicle and about an hour from the nearest town of Catemaco, a small lakeside pueblo known primarily for its shamans. Nobody had a floatation device. Waves like animate limbs rose out of the surface of the water and penetrated my nose, my mouth and my eyes. I told myself to remain calm. I knew I had to swim parallel to the shore and conserve my energy. But my efforts gained me not an inch. I kept moving away from my friends and into the horizon. My friend Becca, the only person who realized what was happening, was staring at me in terror and waving her arms above her head. Suddenly, I couldn’t see her anymore. I couldn’t see the shore. Panic swept through me. I started hyperventilating the ocean into my lungs. I then understood fully — not just intellectually and emotionally but bodily — what the word “drowning” meant.

With every breath of oxygen I managed to take, I heard the gurgling of water in my lungs — a terrifying sound with corpse-like connotations. I had reached an impasse: every neuron in my brain begged me to keep fighting, and every cell in my body screamed that it could not. It was the ultimate mind-body battle; both were losing. The blue Gulf of Mexico stretched out around me endlessly, immensely, indomitably in all directions, rising and falling like a panting creature, a predator intent on devouring me. After a few minutes, the inevitable became clear: I was not going to make it out of this alive. I would die, senselessly, at the age of 22. This wasn’t supposed to happen, and yet it was.

This would be the end of my story.

When I first arrived in Mexico City for my first job out of college, as a newswire correspondent, I took taxis everywhere. It’s unsafe to hail a cab from the street here, particularly if you’re a blonde, green-eyed Gringa. You never know if you’re going to get robbed, raped, or kidnapped. In Mexico City, anybody can become a taxi driver — or taxista — if they have a car and some red and yellow paint. The only safe taxis are called “Sitio Taxis” and you have to call them or find one of their many curbside stations. They’re expensive, but most expats and upperclass Mexicans rely on them.

Experiences that would frighten most people thrilled me — like the time I fled armed drug traffickers while on assignment in the moonlit mountains of the Mexican state of Guerrero…

Driving through traffic en route to my office in the upscale neighborhood of Polanco, the taxistas almost always asked me some variation of the question: “Why on earth have you come to Mexico?” The implication being that any U.S. citizen in her right mind would not move to a country so many people are dying in the desert to escape, “lips huge and cracking,” from dehydration and “burned nearly black” under the merciless sun, as the author Luis Alberto Urrea wrote in his vivid book about migration, The Devil’s Highway. My own father was born in the Mexican capital, but his mother, Carolina, had her eyes on the North since she was a little girl. She and her family eventually moved to the border town of Tijuana, where they could practically smell the green American dream lawns on the other side. After a life of hunger and hardship, they were granted permanent U.S. residency, started a family meat-packing business in San Diego, and were suddenly reborn into the American middle class.

Why on earth have you come to Mexico?

“For my job,” I always responded from the back seat. But the answer was, of course, more complicated than that. There were many answers. One answer was rooted in my DNA, pulsed in the blood my father gave me, the blood that courses beneath delusory light skin:

I have come here because my cause is buried in the swamp of skulls upon which this great metropolis was built.

Another answer was resting inside of the oath all five of us expats made in the car ride to Los Tuxtlas, speeding through a heavy storm, straight into the known territory of notoriously bloodthirsty Zetas. Nick, a fellow journalist who covered the Mexican drug war, had refused to come with us on this trip, convinced we were asking for trouble.

“I’d rather die than live afraid,” someone said aloud as we drove. And in the solemn silence that followed, every person in the vehicle nodded, one after the other. So ignorant and young were we — was I, with my fearless smile.

After the near-drowning, my psychologist diagnosed me with post-traumatic stress disorder. I had recurrent nightmares and daily flashbacks. I had what felt like random sleep apnea: out of nowhere, my body would stop wanting to breathe, my throat constricted against my will, and I would start choking and gasping for breath. Inhalers did not help because this was not asthma. This was death. Death had taken me into its jaws and I had escaped, but I wasn’t supposed to escape. And so death kept hunting me.

I had always been an unusually bold person. Experiences that would frighten most people thrilled me — like the time I fled armed drug traffickers while on assignment in the moonlit mountains of the Mexican state of Guerrero, clutching the bed of a truck as it sped over a bumpy dirt path. Or the time Zeus, a bey Irish stallion I was riding as a 15-year-old visiting Ireland’s Clonshire Equestrian Centre, slipped and fell on mud as we approached a line of wooden jumps on the slope, and the nine horses galloping behind us flew over our fallen bodies, the gray sky blotted out by their soaring legs and bellies. One might say it’s this adrenaline-loving personality that led me to accept a job in Mexico as a foreign correspondent during one of the bloodiest periods in the country’s history.

But the near-drowning in Los Tuxtlas was different. The near-drowning in Los Tuxtlas seemed to have shifted my center of gravity behind me, making it feel impossible to move forward. I was drowning in the memory of the drowning.

I refused to believe that my adventurous spirit had died, however. I started taking swimming classes at the local gym, pausing in the middle of laps to grasp the side of the pool, coughing and gasping as a flashback passed. I went on a guided adventure excursion with friends in the nearby town of Malinalco, jumping from the tops of small waterfalls into river rapids below — wearing a life jacket, of course, but nevertheless pummeled by the force of the water into the river’s bed, which induced panic attacks so increasingly terrible I had to be escorted out of the canyon early. I started taking guitar lessons to distract myself. I climbed mountains. I painted inspiring poems on the walls of my apartment, like “O sweet spontaneous earth” by E.E. Cummings, who writes of nature: “Thou answerest them only with spring.” I bought a motorcycle, a Yamaha FZ16, and learned to drive it. The men in my news bureau, which had a male-to-female ratio of 7:2, found it hard to believe that a girl standing only 5’2″ could ride anything other than a scooter, but every morning I, leather-clad, was their living proof.

A wide-eyed man wearing thick-rimmed spectacles prodded the corpse of a white bird on the ground with his fingers…

But it was all a façade. Inside, I was weak and wounded. I felt permanently tired and afraid. Nothing helped — not the motorcycle, not the swimming, not the mountain-climbing or poetry or guitar. My eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy made the flashbacks go away, but I stopped paying for the expensive sessions when my psychologist insisted on treating me for the “trauma” she was sure I had experienced when I was robbed at gunpoint a few weeks into the therapy.

“I can’t keep treating you for the drowning until I first make sure that you’re completely cured of the trauma from the robbery,” my therapist explained.

“But the robbery wasn’t traumatizing,” I protested. “It lasted like 30 seconds, and for most of that time, I knew I was going to be okay. The guy just wanted my stuff.”

It is one thing to be terrified for a few seconds. It is something else to be certain you are dying and going to die for nearly half an hour of your life.

Friends who heard me talk of the ocean incident afterward expressed relief that something worse hadn’t happened to me. “When you called me crying saying something horrible had happened to you in Los Tuxtlas, I thought you were going to tell me you had been raped,” one said. I have never been raped, so I can’t objectively compare the two traumas. But in my mind, when the sea was penetrating my every orifice, mindlessly, without intent yet embodying an inevitable cause-and-effect that involved sinking and suffocating me to death…it felt like rape. The difference was my attacker was one whose body wraps around the entire planet and is stronger than all ships, all whales, and all continents.

I remained terrified, anxious and depressed. When I had nearly reached the summit of the volcano Malinche recently, I suddenly felt the unconquerable pull of the abyss on my limbs. I clutched the prickly foliage at my feet and curled into a ball on the nearly vertical slope, my forehead against a rock as I battled the vertigo I had never before felt, and I cried, because I realized that the darkness of death had infected my mind in the sea, and that my mind was now incurably sick, hopelessly synonymous with the vastness, the nothingness, trying to yank me to my death — because I had let it be so.

We arrived in Los Tuxtlas when it was raining, so we decided to spend the first night in the mystical town of Catemaco, the lakeside pueblo that attracts travelers who believe in magic and seek to see the local shamans. There were five of us: tan, emerald-eyed Rodrigo, my Bolivian roommate; witty Becca, from England; short, squat Brian, a fellow Gringo; blue-eyed, blonde-haired Paul, a co-worker I had a secret crush on; and myself. But we weren’t there to see any witchcraft. I was the only person in the group curious about it, and had resigned myself to heading immediately to the beach the next day.

“We’re reporters,” I told Paul as we settled into our room at a cheap hotel. “I’m sure we can find an isolated beach somewhere tomorrow if we really dig for the information.”

Expats in Mexico know the country’s Holy Week is the worst time to go to the beach. Celebrating families occupy every square foot of sand, be it a routinely popular tourist spot like Cancun or a lesser-known coastal town like Mazatlán. But in 2011, smack in the middle of Holy Week, Paul had wanted to go to the coast of Los Tuxtlas. He was leaving Mexico City forever in a few days for a job at our newswire’s Sao Paulo bureau, and he wanted to say goodbye to the country in the Gulf of Mexico. We were determined to find an isolated beach if one existed.

We ate dinner at a restaurant by the lake, where a wide-eyed man wearing thick-rimmed spectacles prodded the corpse of a white bird on the ground with his fingers. Beside us, a crocodile in a cage was covered by dozens of small turtles that crawled all over its body. “Why doesn’t the crocodile eat the turtles?” I asked nobody in particular. “Because then he’d be bored,” Brian answered.

From our table, we could see the silhouette of a man who seemed to be sitting weightlessly atop the surface of the Catemaco lake. He had a fishing pole in his hands and his legs crossed on the water. We couldn’t make sense of the sight, and eventually we gave up trying.

We headed into town to investigate where to go the next day. We came across a stone building that lacked a front wall; the fog drifted in and out of it as though it were the building’s breath. We walked inside and discovered it was a bar. We ordered some beers. The bartender was a blonde German expat, and I asked her if she knew where we might find an uncrowded beach. “She wants a beach with unicorns and waterfalls and fairies,” Paul joked, because he likes to make fun of me ever since I told him I was obsessed with the fantasy books as a child. The bar owner leaned over, smiled mysteriously and told us she knew how to find what we were looking for. She drew us a map. “A few minutes after the signs for Playa Jicacal, you’ll see a dirt path leading into the jungle. Take that road until it ends. You’ll see an abandoned hotel there. Then get out of the car and look for a staircase leading into the jungle.”

The next day, we got lost. Paul and I bickered the whole way.

“I have a gut feeling that you’re going the wrong direction,” I said.

“Oh really?” Paul said angrily, making a sudden U-turn. “Since you have a gut feeling, then you must be right. From now on, I won’t make a single turn unless your gut tells me to.”

Paul and I had a mutual love of Jon Krakauer’s nonfiction books, Double Stuf Oreo’s, and rock climbing, but in almost every other aspect, we were opposites. I was intuitive, he was logical; I was spiritual, he was agnostic; I was right-hemisphere dominant, he was left-hemisphere dominant. It was because of those differences that I felt I could never confess to him how I felt about him, even though I was pretty enamored from the moment I met him at the office. He was a few years older than me and handsome in the quintessentially American way. We ate lunch together almost every weekday and often travelled together on weekends. But I was sure I was not his type, and anyway, he was leaving now. Forever.

“There is so much sexual tension in this vehicle,” Brian announced from the backseat. “Will you guys just have sex already, please?”

We ignored him. At some point, I fell asleep. When I awoke, we were on a bumpy dirt path in the middle of the jungle. It was almost sunset, and the golden light drifted through the dense treetops in thick hazy lines. Butterflies the color of butterscotch floated in the air. After about 15 minutes, the road ended at the top of a mountain, where we found three crumbling white buildings with spiderwebs in the windows and a stone well. We parked, got out of the car, and heard the sound of monkeys hooting in the trees.

Suddenly, we heard rustling from behind us. A large Mexican man with dark, leathery skin and a missing arm emerged from the jungle. “You looking for the Hidden Beach?” he asked in Spanish.

We nodded, nervous, wondering who he was and why he was there all alone. The thought crossed my mind that perhaps he was a jungle-dwelling shaman, and I had to fight down the urge to interrogate him. He pointed behind him. “Down that way,” he said.

He was convinced the U.S. government was conducting mind-control experiments on him.

We walked into the trees. There, inside the jungle, we found the stone staircase. Too excited suddenly to care about who the man had been, we descended the side of the mountain and after about 15 minutes we arrived at a completely abandoned beach.

“Ladies and gentleman, we have just found the only Mexican beach without a soul on it this weekend,” Paul said.

The sand was covered in a moving, pearly carpet of crabs that we displaced with every step. As darkness descended upon us, we quickly set up camp, pitching our tents and gathering dry wood for a fire. A chorus of insects made a foreboding sound, like an E flat that seemed to rise endlessly in pitch. Strange, glowing insects that were not fireflies gathered around our fire, fainting occasionally in the smoke. “Look, it’s the fairies you’ve always dreamed of!” Paul said jokingly. But even he was perplexed: the flying black bee-like bugs seemed to have two blue glowing lights in front of their bodies. We couldn’t figure out what species they were. Paul scooped up one that had fallen into the sand and inspected it in his palm. “Those are its eyes,” he said, mystified. We followed them around and watched them glide over the sea and twist in and out of the foliage on the mountain. We tried to keep them away from the smoke, which seemed to make them sick. Becca said, “They’re protecting us.” Brian snorted, retorting: “Either that or they’re warning us.”

We passed around a bottle of mescal, shared stories of our adventures, then fell asleep.

The next morning, I went for a swim. Becca followed me. We took our bikini tops off, wanting to feel the seawater against our skin. All around us, gold particles winked in and out of existence on the water. I threw my head back and felt free. On the mountain behind our beach, a clearing in the jungle revealed a herd of sheep grazing. “It’s like a scene straight out of the Bible,” I told Becca, breathless.

When I turned around to look at Becca, I was disoriented. A few seconds ago, she had been right beside me. Now she was many meters away, and getting farther. I was the one moving.

I could no longer feel the ground under my feet. I tried to swim toward Becca, but I just kept drifting away from the shore. I knew I was in a rip current and that I had to remain calm. But the knowledge that my life suddenly depended on my ability to do that made it difficult. I’d never been a good swimmer. I could do the breast-stroke and tread water for a minute or two at a time, but I tired easily. My heart pounded frantically and I hyperventilated as I tried with all my might to stay afloat. I exhausted my strength. I started to breathe and swallow water. And that is when I started to drown.

This can’t be happening, my brain screamed. But it was. I realized with terror that I was as mortal and insignificant as the lamb grazing on the mountain.

After about 10 minutes, I couldn’t fight anymore. Although every cell in my brain resisted the idea of dying, it seemed the only possible outcome. A profound sadness weighed me down; warm tears fell out of my eyes. My only consolation was the realization that drowning was not going to hurt, at least not physically. My lungs were filling up with water, but they didn’t feel pain. What was awful was the terror, the helplessness, the loneliness, the destructive discovery that I was of no objective value to the apparently unthinking universe. I thought of my mother, who had never wanted me to go to Mexico. My mother, born on the island of Puerto Rico, moved to the U.S. in her 20s, like my father, in search of the American dream. She was a doctor, an internist who had set up her own private practice recently in San Diego. She was a strong, independent woman who supported me and my sister alone because my father left when we were little girls. She paid for me to go to private school all my life, bought me a horse, and paid for my equestrian lessons. She gave me a life of privilege. When I graduated college and told her I was moving to Mexico, she cried.

When I moved, I hoped to understand my father. An adventurous, eccentric man who could be tied down by nothing, my father disappeared from our lives for many years. When I was 12, he was locked up in a mental institution because he was hearing voices that nobody else could hear. He was convinced the U.S. government was conducting mind-control experiments on him. When he was released, he drove south across the border into Tijuana, parked in front of a jail with his arms in front of him, and begged the officials on guard to handcuff and arrest him. “Help me,” he begged. But even in the jail cell, using a milk gallon as a pillow, the voices plagued him. And so he left the country, seeking political asylum in various countries of Europe, then Asia. My father had always been an enigma, and I hoped his country would help me understand him. I did not exactly believe my father was crazy.

But now, as I came face-to-face with my mortality, my eyes stinging underneath the dark ocean, it was my connection with my mother that I felt most intensely. I could not bear to imagine the pain she would feel when she was informed that her eldest daughter had drowned. After everything she had done for me, she would lose me, and all because of my stupid mistakes, because of my naive belief that a short, adventurous life was better than a long and peaceful one. No! I thought, and it was my mother’s voice, an outburst that coursed through my veins like a bolt of electricity that sent me breaking once more through the surface of the sea.

Then I saw blonde hair up ahead. It was Paul.

His face was full of terror. “What’s going on?” he asked, trying to sound casual.

“I’m drowning,” I gasped.

“You’re going to be okay,” Paul said.

His face betrayed his fear and uncertainty, and I was horrified he was going to leave.

“Please don’t leave me,” I begged.

The shore was so far away, it looked like the coast as I saw it from a cruise my grandmother paid for me to go on shortly after graduation: a beautiful, inaccessible paradise one would never be mad enough to try to swim to. “Don’t look at the shore,” Paul said.

“I’m going to die,” I said. With every breath, I could hear the ocean’s deadly gurgle in my lungs. The sea heaved its limbs mercilessly into my mouth.

“You’re going to be fine,” he said. “I won’t leave you. But I need you to backfloat.”

I had never been able to back-float before. Earlier that morning, I had actually said to Becca, “I couldn’t backfloat to save my life.” Paul put his hand under my back and helped me. Water entered my lungs with ease. I swallowed as much of it as I could to avoid choking.

“Please don’t leave me,” I said.

“I won’t.”

Many people, when they’re drowning, hurt the people who are trying to save them. They claw at their faces, push them underwater. They do this because panic is something that destroys rationality. Panic can make a drowning victim so hysterical that she ends up drowning both herself and her would-be savior. Somehow, I was able to keep enough of a rein on my panic that I did not hurt Paul.

I begged my stomach to be big enough to contain the whole sea if necessary. I was topless and utterly vulnerable. I thought of how strange it was that Paul was seeing my breasts under these circumstances. I was terrified he was going to give up or drown, too.

He warned me every time a wave was coming so that I would hold my breath. Sometimes it worked. Most of the time, I drifted in and out of consciousness.

“I can feel the ground!” I heard him say suddenly. I did not believe it. He tried to let me go, and I clutched to him in desperation. Suddenly, he was dragging me toward shore. “Brian, your shirt!” he shouted. Brian came running.

I crawled as far away as possible from the water to cough and vomit seawater. Becca patted my back, tears running down her face. “We couldn’t see you for so long!” she sobbed. “We thought you guys were dead.”

Afterward, Paul would tell me that in all his years of surfing, he had never experienced a rip current so wide or so fast. He decided, when he jumped into the ocean to save me, that he was either going to come out with me or not at all. For a long time, he wasn’t sure which one it was going to be.

As I lay on the beach trying to recover, I realized that something strange had happened to me, something I wouldn’t understand until reading Moby Dick many months later. I didn’t feel grateful to be alive. In fact, I didn’t feel alive at all. Although Paul had clearly saved me, I felt dead.

“The sea had jeeringly kept his finite body up, but drowned the infinite of his soul,” Melville writes of the sailor Pip after he sees the ocean stretching out endlessly in all directions, and goes insane.

Paul left three days afterward. He let me sleep over at his house the night before he left. The near-drowning had so thoroughly messed with my neural wiring that my belief that my life depended on Paul for some reason extended beyond the incident, and I felt certain that once he left Mexico City, I would die. I could not survive on my own. But he was leaving in a few hours and there was nothing I could do.

I lay in his bed with him, watching the Mexico City skyscrapers from his open windows. Their lights remained on all night. I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t breathe correctly. I was filled with a highly unpleasant electricity. Suddenly, Paul pulled me against him. I froze. “Does he think I’m someone else?” I wondered. “Is he conscious?” I tried not to breathe or make a sound. I did not move until the sun came up.

We said goodbye without smiling or crying.

My nightmares were almost always the same. I’m back at the beach, and the sea level begins to rise. I turn to face the mountain behind the beach, and use the foliage on it to climb. At the top of the mountain, there’s a gate too tall to climb. Suddenly, I find a doorway. But it is locked. I can see that Paul is behind it, and I beg him to open the door as the rising ocean approaches my feet. He shakes his head. “You’re going to have to find your own way, this time,” he says.

But I can’t, and I drown.

My first interview as a journalist in Mexico was with a then-spokesperson for the Agriculture Ministry. We had breakfast at the diner Vips, the Mexican equivalent of Denny’s. He asked me if I had always wanted to be a journalist, and I mentioned that what I really wanted was to write magical realist novels someday.

He smiled and shook his head. “Novels? What you write won’t even have to be fiction. In Mexico, things happen that don’t happen anywhere else.”

A few months after the near-drowning, I fell down an open sewage hole. I was wearing a golden Bebe dress and glittery, three-inch heels in the upscale neighborhood of Polanco, looking for a Sitio Taxi after spending a few hours at a club called “Joy.” Suddenly I was plummetting into the depths of Hell.

Luckily, I opened my arms just in time to stop my fall before I disappeared forever. Jose Ignacio, a tall, handsome Venezuelan with a shaved head who was my companion that night, pulled me out and offered to accompany me to the hospital when he saw my bloody shins, scraped by the sewage hole’s concrete walls during my descent.

I politely declined. I wanted to go home. This was an omen if ever there was one: Mexico wanted me dead, and would swallow me whole if it had to.

I flew to the Mexican state of Oaxaca, to Puerto Escondido, to de-stress. I needed some time alone on the beach, to breathe and soak up the sun. When I arrived in the evening, I had barely checked into my hostel when the electricity in the entire port went out. It rained for the first time in many months, coming down in a torrential pour that wouldn’t stop. The next day, the sea level started to rise. I stood on the shore, trying to deny the terror as the waves crept closer and closer and then enveloped my feet. I watched the clouds turn purple and gray and unleash lightning that danced upon the sea. Even the locals were dumbstruck, taking pictures on their cell phones, calling their family members: “Estas viendo esto?” Are you seeing this? I went online and checked the National Hurricane Center’s web site. The probability of a hurricane in the next 48 hours was 40%. A few hours later, it was at 60%. My flight back to Mexico City wasn’t for another week, but the sounds of the waves cracking like the whips of an angry God and the thunder and howling wind hurling itself against my cabin walls terrified me. I bought an extra flight back and left the next morning. The Associated Press reported the next day that an American surfer had died on the same beach where I had stood staring at the lightning strike the rising water. The waves had pulled him out to sea and drowned him.

My Mexican friends nicknamed me Juanita because my real name, Jean, is so hard to pronounce here (“Yeen? Yehan?“). I had no idea that my great, great grandmother was named Juanita until I went to ask my grandmother’s 90-year-old brother, Goyo, about my family history a few weeks ago. He lives alone in Mexico City.

Goyo, lucid and articulate for his age, explained that my great, great grandmother, Juanita Valenzuela, was a shaman who lived in the valley of Tlaltenango in the central Mexican state of Zacatecas. She was a descendant of the indigenous Caxcans who initially inhabited the mountain-rimmed region and who fought the Spanish conquistadores in multiple devastating battles throughout the 16th century. Juanita married a Spanish immigrant, and gave birth to three sons: Trinidad, Isidro and Antonio. The townspeople relied on her for spiritual guidance and healing. She cured the sick, communicated with her neighbors’ dead relatives, and most miraculously, identified criminals in her mind, so that when the townspeople came to her seeking to recover a stolen cow or horse, she would tell them where to find their livestock. According to Goyo, she was always right.

But Juanita was a fickle woman, and when news of the Mexican revolution rippled through the countryside, she ran away to fight, abandoning her sons. Their father tried to raise them on his own, but largely neglected them; they grew accustomed to sleeping in barns and scavenging. They never went to school, and weren’t even literate.

Antonio, the youngest, decided he wanted to come to the United States of America. Lighter-skinned like his father, with golden eyes, Antonio was a handsome man with big ambitions and a wild character. Several times he made his way across the border to participate in the California crop harvests, to help lay railroad tracks, or to work in the mines. He was willing to do anything to make it in the U.S., the land of dreams. But one day, a slave he was playing cards with asked him to please stop humming. Antonio’s volatile temper flared, and he slashed him with a razor. My great grandfather was sent to San Quentin prison, then transferred for unknown reasons to Alcatraz, where he spent several years and taught himself to read and write in both Spanish and English. When he was released, he returned to Mexico and fathered my grandmother Carolina, who mothered my father Marco, who inherited Juanita’s ink-black hair.

I returned to the beach during Holy Week for the anniversary of my near-death experience with two friends, a large piece of cardboard, a knife and a marker. I was determined to give the deadly beach a name — one that would give it a positive connotation in my mind and stop the nightmares.

This time, the beach wasn’t abandoned. A Mexican family was in the water and they were all drowning. We could see them as we descended the stone staircase. A rip current was pulling them into the sunset. By the time we reached the sand, they had reversed course. When they emerged on the beach, gasping for breath, gagging and puking, one of the little boys joked, in Spanish: “Go on in, the water’s great!” I smiled. Then I hopped into the ocean and swam.

A photo from that day shows me next to the sign I later built, my hair wet, triumphant arms in the air, clutching a knife in one fist. I had improvised string from dry grass and used a fallen bamboo stick to make the sign. “Playa de las Hadas,” the sign reads in the photo. Beach of Fairies. On the backside, in Spanish: Beware of rip currents.

Two months later, in June 2012, my friend Armando “Mando” Montaño came to Mexico City to intern with the Associated Press. Mando was a boundlessly energetic 22-year-old I met while interning at the Seattle Times in 2008. He constantly “liked” my photos of Mexico City, told me he wanted to follow in my footsteps, and eventually secured his dream internship and came to live in the same building as me in the upscale neighborhood of Condesa.

Mando knocked on my door when he arrived, and I opened it to find his thick dark hair, high cheekbones, and broad smile barely changed from the last time I saw him. He immediately swept me up into an aggressive hug and gave one of his uniquely rambunctious laughs. The building was full of other expats, and right away I introduced him to all of my friends, who fell in love with him. He asked me what the gay scene was like in Mexico City and I informed him that I had no idea but that I was happy to accompany him to the gay bars and find out. We went dancing together every weekend. “I feel like I’m seeing Mexico City for the first time all over again, through your eyes,” I told him happily. I was starting to feel good again, for the first time in many months. Mando’s arrival signaled a new phase, one of aliveness once again. He was endlessly positive and ambitious. We lay on my bed many hours, exchanging stories of lost loves, of journalism dreams.

“Someday, you’re going to be the editor of the Wall Street Journal, and I’m going to be the editor of the New York Times, and we’re going to change the world,” he said, only partly joking.

One Friday night, while I was obsessively reading The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand, he came over and begged me to come out — everyone in the building was going bar-hopping.

“I am way too obsessed with this book,” I explained. All I felt like doing that night was to stay in bed binge-reading and drinking hot chocolate. He sighed.

“Alright, fine — but if you change your mind, let me know. Either way, I’ll see you at the election on Sunday? The AP is letting me contribute some coverage!” he said, clapping his hands.

“Wow, I’m so proud of you!” I said. “I can’t wait.”

It was the last time I would ever see him. The next day, Saturday, I checked my emails from bed and discovered I had a message from his mother, asking me if I was aware that Mando had had “an accident.” Immediately, I called Mando multiple times, thinking perhaps he was in the hospital because he had gotten hit by a crazy driver or something. I ran upstairs to his apartment; the door was open because the cleaning lady was mopping. His bedroom door was also open, but he wasn’t in there. I went back downstairs and called Mando’s mother, who informed me that Mando was dead.

His body had been found crushed in the elevator shaft of a building on my block.

I could try to explain what it feels like to be told that a person as alive as Mando is actually dead. How the word “dead” feels like a piece of raw meat in your brain, completely out of place, totally impossible to integrate. How you know it’s an offensive joke or a lie but you can’t understand why someone would make that joke or lie, especially his sweet, beautiful mother. But it is impossible to do justice to the violence of such knowledge.

The police investigation continues. Nobody, it seems, will ever understand what happened — why he was in that building where he didn’t know anybody, why or how he got into the elevator shaft.

On Sunday, election day, my editor sent me to the headquarters of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, to get video coverage. He and many others were certain that the PRI candidate, Enrique Peña Nieto, was going to be the next president of Mexico. I tried to distract myself by focusing on my work. As I stared at the video screens in the media room, my roommate called me. “They say the official cause of his death was asphyxiation,” she said, crying. My heart stopped. Dozens of reporters were suddenly rushing past me and out the door. Enrique Peña Nieto was about to make his speech after having been declared winner of the Mexican presidential election. I followed with my video equipment, trying to get to the stage, trying to ignore what I had just heard. A security guard stopped me and several others in our tracks. “Passage is closed as of an hour ago,” he said. “There is no more access to the stage.” I tried to argue. But as I spoke, I could hear my voice getting increasingly hysterical, and I found it suddenly very hard to breathe. The booming sounds — of screams, of drums — were strangely rhythmical. It was unmistakable: I was hearing the sound of Mando’s heart, pounding faster and faster as he ran out of air during his last moments. I knew exactly what it felt like not to be able to breathe. I had felt it — the terror, the loneliness. The pounding sounds all around me continued to accelerate, until it seemed that they could accelerate no more, until it seemed all the beats were running together in one terrible scream. And then the sounds stopped.

I don’t remember what happened exactly after that, but when I came to, I had an oxygen mask on, and there were paramedics all around me. “Breathe slowly, deeply,” they said. “You’re fine. Just breathe.”

“There is no quality that is not what it is merely by contrast,” wrote Melville so many years ago in Moby Dick. I highlighted and starred this sentence in the book.

Why on earth have you come to Mexico?

So many reasons. My job, my father, my thirst for adventure. Because of the quote, which I had not yet read but believed in: There is no quality that is not what it is merely by contrast.

The first 22 years of my life were immensely privileged. I lived in Southern California among the small percentage of human beings on the planet with a U.S. citizenship, a college degree, and no debt. I moved to Mexico, in part, because I wanted to discover the other side of life: hardship, suffering, chaos. I moved to Mexico because I believed, like Melville, that the poetry of a sunset is in the entanglement of night and day, in the limbs of darkness yielding fully to the dark. I moved to Mexico to unshelter myself: to discover death, and through it, life.

What I didn’t expect is that discovering death would make me terrified of living. That discovering death would create in me a fear that would make it impossible to enjoy things that once gave me joy.

So my fight continues. My last weapon is probably my strongest. Words, after all, have long been humankind’s tool for making sense of chaos. With the ropes of letters and the chains of ink, I capture the vastness of the indomitable incomprehensible. I imprison the darkness, and impart its meaning to you: a panther in a den that cannot prey.

For words are indeed magic, a manner of supernaturally influencing reality. With them, I can change the world without touching it — like Juanita, the woman whose name Mexico bestowed on me, who gave my father hair as black as ink.

9 Comments

Error thrown

Call to undefined function ereg()